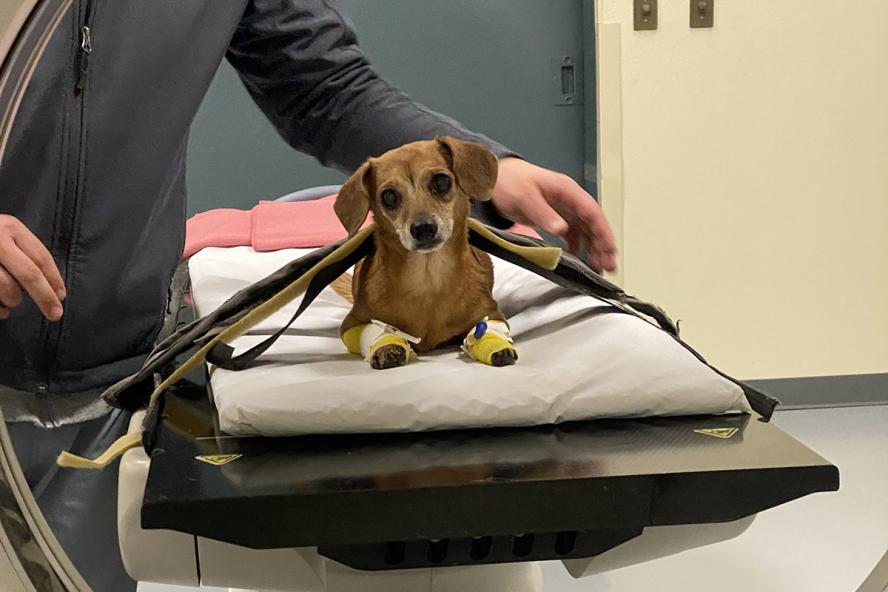

Stella, a 13-year-old mini Dachshund/Chihuahua mix owned by Liz Paolucci, was referred to Foster Hospital by her primary veterinarian. Her recent medical history included loss of appetite and an elevated white blood cell count, according to Heil. Stella’s issues progressed over about 10 days to labored breathing and the development of a lump on her side.

“I brought Stella to her regular vet, where they did an x-ray and saw a metal skewer,” Paolucci said. “I overheard her vet on the phone with someone at Tufts and he said, ‘She’s fine, but I don’t know how.’ That made me nervous because I thought that I might lose her.”

Upon recommendation, Paolucci brought Stella to Foster Hospital’s Emergency Medicine & Critical Care (ECC) unit. ECC enlisted the help of the Diagnostic Imaging Department, where Heil was surprised when first shown the x-ray. “She’s a little dog and it was amazing how she got it [the skewer] down,” she said. “On the image, it looked likely to be puncturing out of her stomach and probably into her lungs.”

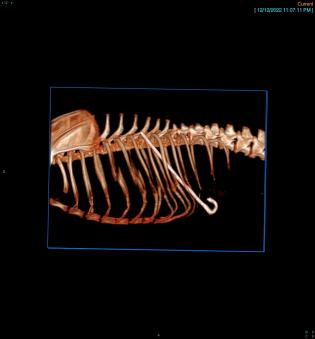

Stella was sedated and a Computed Tomography (CT) scan was conducted. “In this case, we did the CT for planning purposes, so the surgeons won’t have questions and know what they’ll be doing,” said Dr. Leah Pomerantz, another diagnostic imaging resident. “It helps to assess the extent of the damage and what the surgeon may encounter during the procedure.”

The CT revealed that “a metal skewer, about four inches long, was puncturing out of her stomach, through her diaphragm, her lungs, in between two ribs, to the lump on her side,” Heil explained. “Things were inflamed around it, but it wasn’t as bad as it could have been.”

To Heil’s surprise, Stella seemed relatively unaffected by the situation. “For her, the area was tender to the touch, but she was in good spirits,” she said. Unfortunately, it was determined that the skewer would need to be removed surgically.

After consulting with surgeons, despite her age, Stella was put under anesthesia so the skewer could be carefully removed. A thoracotomy and an abdominal exploratory surgery were performed by the surgical team because the skewer was going across both the chest and abdominal cavities.

Fortunately, the procedures went smoothly. Stella recovered quickly and went home just a few days after the surgery. “I was told that Stella’s recovery would be hard, but she should be OK,” said Paolucci. “And she is. She was fine about a week after the surgery.”

Paolucci is thrilled that Stella remains by her side. “No one knows how she swallowed the skewer and how it didn’t kill her is beyond me,” said Paolucci. “She weighed about 10 lbs. before surgery and six after it, so we had to fatten her up again, but we did it. Now she’s my sword-swallowing miracle. Please thank all the doctors from the bottom of my heart.”

Due to a considerable amount of luck that limited damage and the collaborative work of many, Stella is still wagging her tail. “Surgical Resident Dr. Valeria Colberg removed the skewer, CT technician Josh Peters provided CT images and 3D reconstructions and our ER/ICU and anesthesia teams kept Stella safe and stable,” said Heil. “It was a team effort.”

The appeal of working in diagnostic imaging

Diagnostic imaging was a key component to the success of Stella’s case, as it is in many others. “This dog presented with a mass on her side, so it could have been a cancer that is bleeding and infected or an abscess,” Heil said. “Without imaging, we couldn’t tell what was wrong.”

Often playing a role between a visit to the ECC and either surgery or another specialty, diagnostic imaging can provide important information about the size, shape, and location of organs and structures within the body. This helps clinicians determine a diagnosis, which leads to a treatment plan devised by a collaborative veterinary team.

The variety of this professional collaboration and the sundry species encountered drew Heil to this veterinary specialty. “We work with every modality,” she said. “We can see how it works in different cases and apply principles to various disease states.

Pomerantz added, “I like having my hands in a lot of different cases, from the emergency department when you need to find out answers fast for a critical patient, to working with the teams in neurology, internal medicine, or ophthalmology, among others.”

Heil also leaned toward Cummings School due to Dr. Trisha Oura, V08, a mentor during her internship, and a former Tufts faculty member. “She was an excellent teacher who provided great support and was really inspiring,” Heil said.

Dr. Mauricio Solano serves as section head of the School’s diagnostic imaging service. “Several of our graduates have served as faculty members at academic institutions in the American Veterinary Medical Association system,” says Solano. “I like to think they share the same passion for teaching new generations of students as my colleagues have shown over the years.”

Solano also recognizes the contributions of veterinary professionals who completed residencies at Cummings School, noting “Our former residents have made, and are making a difference in diagnostic imaging across the globe. From well-regarded imaging book authors to people working tirelessly in worldwide veterinary imaging organizations that oversee our specialty.”

Diagnostic Imaging at Cummings School

According to the American College of Veterinary Radiology, 21 U.S. veterinary schools and colleges offer diagnostic imaging residency programs. Cummings School’s diagnostic imaging service is one of the largest in the country, with six board-certified radiologists who maintain active research programs that advance state-of-the-art knowledge in the imaging field.

Its internationally renowned diagnostic imaging residency program provides training in routine and special procedures in small and large animal diagnostic radiology, ultrasound, nuclear medicine, CT, and Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), using the most advanced imaging equipment available.

“We are renowned for maintaining research programs that advance state-of-the-art knowledge in our profession, from clinical ultrasound in small animals to equine MRI tendon diseases,” Solano explains. “Our faculty and staff share a common desire to collaboratively teach new generations of students and radiologists the art of imaging as a critical diagnostic tool to improve the life of our patients.”

Current residents attest to the committed approach to teach and learn from all team members. “Getting perspectives from different experts is an invaluable experience and a huge advantage,” Heil shares.

Pomerantz applauds the teamwork. “Our mentors are highly knowledgeable and experienced, yet they still discuss cases with us and want our opinions,” she said, noting that residents are encouraged to conduct research to gather more information for a case, and then share it so the radiologists may learn something new. Residents, in turn, adopt that style, so when they are teaching students they are empowering them as well, and working to figure things out together.

“We approach cases with humility and come to a decision that is sound in our experience and evidence,” Heil said. “And we are not looked down upon if we make mistakes. It’s part of the learning process.” Pomerantz believes that this approach is common throughout Cummings School, where mentors and faculty strongly embody collaboration. “They are all highly approachable and interested in discussions.”

Both Heil and Pomerantz enjoy being at the heart of the operation to serve their animal and human clients. Heil summarized, “Everyone needs radiology at some point. All the different teams come together here, share what they see, discuss options, then decide what to do next.”