-

About

- Leadership & Faculty

- News & Events

-

Admissions

-

Academics

- Graduate

- Advanced Clinical Training

- Continuing Education

- Academic Departments

- Academic Offices

- Simulation Experiences

-

Student Life

- Offices

-

Research

-

- Transformative Research

- Centers & Shared Resources

-

-

Hospitals & Clinics

- Emergency Care

- Hospital Services

-

Community Outreach

- Volunteer

Getting Answers

Histology Lab helps identify disease while blending science with award-winning art

Histology Lab helps identify disease while blending science with award-winning art

“The Histology Lab is where doctors get their information to diagnose diseases such as cancer,” says Katelin Murphy, describing the crux of her work as one of three histotechnology professionals (or histotechs) at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University.

Before a veterinary pathologist can analyze tissue samples to search for abnormalities and diagnose disease, they rely upon histology. Histology is the study of the microscopic structure of tissues, which helps to identify and understand disease processes.

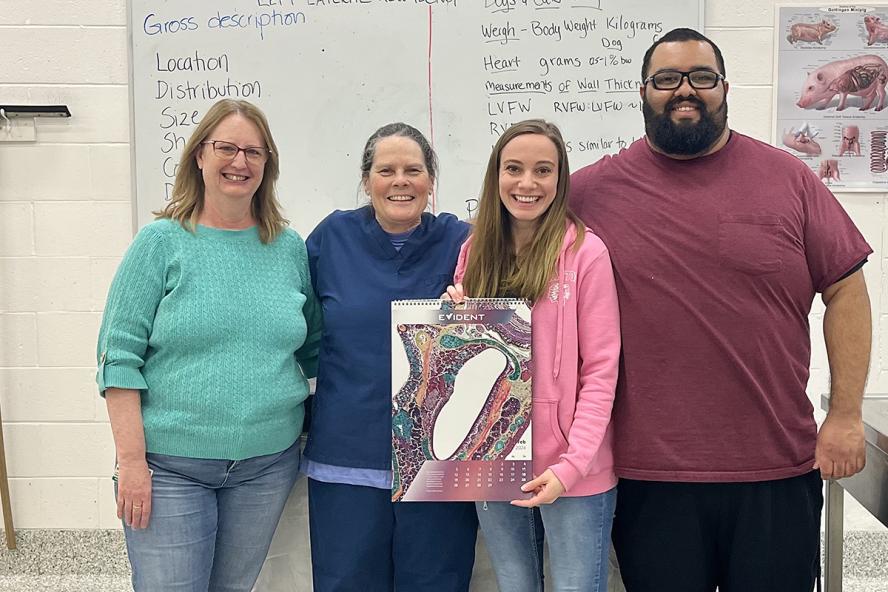

At Cummings School, the Histology Lab is part of Cummings Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. Histology Lab Supervisor Linda Wrijil and histotechs Murphy and Ephraim Gonzalez are supported by Karen Baldwin, a post-room technician who works in necropsy (animal autopsy).

“Cancer is a malfunction of the cells,” Murphy explains. “We’re looking to see how a disease process, virus, bacteria, or fungus is affecting the tissue, what tissues they are affecting, and whether it’s spreading. From this information, a doctor makes a diagnosis and offers treatment options.”

Processing samples

Biopsies begin at the hospital, where a sample of organ or tissue is sent to the Histology Lab in a jar of formaldehyde, Murphy says. Once received, a histotech then dissects pieces of the sample to fit into a small, compact container, called a cassette, which is loaded into a processor. The processor takes the sample from the starting solution (formaldehyde) and rinses it through a series of alcohols, ending in hot paraffin wax. After processing is completed, the sample is embedded into a mold with more paraffin wax, which then cools to protect it and prepares it for the following steps.

The histotech then slices very thin sections off the face of the wax mold using a microtome. “We want the section of tissue to be just one cell layer thick, so you’re not seeing a bunch of cells stacked up on top of each other when you look under the microscope,” Murphy explains. These thin slices (five microns thick) are placed on glass slides and stained with dyes to change the color of the tissue and make abnormalities visible under a microscope. The slides are finally sent to a pathologist for analysis.

“All samples receive a standard stain,” Murphy shares. “After reviewing it, doctors can request the application of a special stain.” Each of the approximately 25 staining options available highlights specific aspects of the tissue. The doctors are looking for structural abnormalities in the cells, or possible signs of an infection from a fungi or bacteria. While most of the stains result in two colors, Murphy has identified a favorite which has led to some stunning results.

“The Movat Pentachrome stain is my personal favorite because it’s the most colorful stain that we offer. But the doctors do not request it as often as some of the other techniques,” she says. “It’s typically requested in research on heart tissue. It can identify many aspects of the veins and arteries within the heart.”

Blending art and science with award-winning results

Pentachrome produces visually stimulating results, including some award-winners for Murphy. Most recently, she earned an honorable mention in an annual scientific imaging contest sponsored by Evident Life Sciences. Murphy’s was one of just 15 images to receive recognition, among 640 images submitted. Her dorsal view of a red-backed salamander skull was stained using the Movat’s pentachrome technique.

Murphy created an Instagram account for her histology images about five years ago. “It was just an account to share all the pictures I was collecting on my phone. Then one day the account blew up when Evident reposted some of my pictures,” she says. Intrigued by the response, Murphy reached out to the company and started a conversation with them about this unique blend of science and art.

“I enjoy submitting my images to different microscopy competitions,” she shares. “I just wanted as many people to see them as possible, to bring attention to the field. That was my goal.” Although Murphy will occasionally borrow an advanced camera from a colleague to photograph the images she produces, her standard method is rather rudimentary. “I stand at the microscope and hold up my smartphone to the lens, and take the picture through there. Many of the pictures that I take I share on social media.”

Murphy admits that while the ability to produce captivating images is a fun and creative aspect of her work, she finds that providing answers to those in need is most important.

“Sometimes the work we do can be sad or difficult, but we’re getting answers for those who need them,” she says. “It’s rewarding to help people and animals.”