-

About

- Leadership & Faculty

- News & Events

-

Admissions

-

Academics

- Graduate

- Advanced Clinical Training

- Continuing Education

- Academic Departments

- Academic Offices

- Simulation Experiences

-

Student Life

- Offices

-

Research

-

- Transformative Research

- Centers & Shared Resources

-

-

Hospitals & Clinics

- Emergency Care

- Hospital Services

-

Community Outreach

- Volunteer

Back to Monkey Business

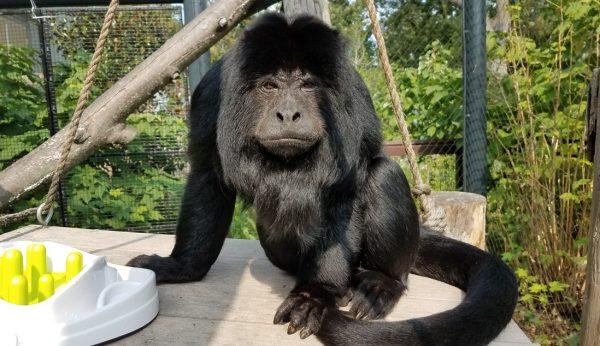

Howler monkey Ramone returns to family at Roger Williams Park Zoo after successful Cummings School surgery

When Ramone speaks, he’s difficult to ignore. Considered the loudest land animal in the world, black howler monkeys boast a call that can be heard up to three miles away and can reach up to 140 decibels—nearly rivaling a jet engine at takeoff (150 dBs).

The staff at the Roger Williams Park Zoo are relieved to have the 19-year-old back in the zoo’s interspecies exhibit, which includes howler, saki, and titi monkeys. “They’re interactive and really fascinating to watch,” says Zoo Veterinarian Jessica Lovstad, D.V.M..

Following a successful surgery at the Henry and Lois Foster Hospital for Small Animals at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University to address a suspected complication from his kidney disease, Ramone has returned to his habitat, where he has smoothly reintegrated with his three children, but not his mate, according to Lovstad.

“He’s a calm, patient animal and a good father,” Lovstad explains, “but he’s had lots of scuffles with his female mate, which go back to pre-surgery. She’s very spirited and they butt heads as to who’s in charge.”

Ramone’s medical issue

Diagnosed with early-stage kidney disease during his annual physical last fall, Ramone was treated with medications and fluids for a couple months, according to Lovstad. When he exhibited some signs of depression and dehydration, Ramone was anesthetized and treated with subcutaneous fluids to rehydrate him, and his kidney levels were closely monitored.

Following some signs of improvement, Ramone developed lameness in his right leg. Different pain medications were unsuccessful, so he was anesthetized for a procedure to determine the cause, which revealed a small tear in his femoral artery, Lovstad says. “A balloon of blood formed in his inguinal area, where his leg and body meet. It was a functional obstruction so he couldn’t move normally and was uncomfortable.”

Lovstad and Kim Wojick, A01, V06, the senior veterinarian at the Zoo, concluded that most likely Ramone’s blood vessels had weakened due to calcium deposits that had formed. His blood pressure elevated due to the kidney disease, and he couldn’t withstand multiple days of blood draws to recheck it. “When this happens to humans, they’re managed either by compression, a coil placement, a thrombin injection, or surgery,” Lovstad explains.

A rare condition for a monkey, Lovstad consulted with a human interventional radiologist after discussions with veterinary cardiologists and internists were unfruitful. “The human specialist looked at Ramone’s images and said surgery was needed,” she shares.

Collaborating with Cummings School

In addition to their position at the Zoo, Lovstad and Wojick teach exotic medicine courses at Cummings School, which they determined would provide the best opportunity for Ramone’s care. “When we get cases at the Zoo like this that require advanced surgery or a specialist that we don’t have access to, we usually turn to Tufts,” Wojick contends. “It’s a great resource to go beyond what we are capable of doing at our own hospital.”

Lovstad collaborated with Foster Hospital, where its cardiology and surgical teams planned to repair the arterial-venous fistula in Ramone’s inguinal region. Surgeon and Clinical Associate Professor Robert McCarthy, V83, and Cardiologist and Professor John Rush led the teams, supported by Anesthesiologist and Assistant Professor Rebecca Reader, V13.

Reader has worked with the Zoo’s veterinarians on a few cases and enjoys the collaboration, which has included procedures on a range of species, including a red panda, river otter and harbor seal. “Bringing a monkey here requires a coordinated effort to ensure the safety of everyone in the hospital during his visit. Ramone was a very good patient, and everything went smoothly,” Reader says.

The day prior to surgery, the Zoo’s veterinarians anesthetized one of Ramone’s sons to collect blood, which they wanted to have available if needed. “We did that as a safeguard,” says Lovstad. It was used for a transfusion during the procedure.

Unfortunately, due to the weakened state of Ramone’s blood vessels, the team was unable to repair the tear as intended. “So, they tied off both his femoral artery and vein,” Lovstad asserts. Wojick adds, “We are relying on the collateral vessels that run parallel for him to maintain function of that leg.”

Recovery has been steady, and despite some atrophy and decreased range of motion in his leg, he is climbing and reaching without issues, according to Lovstad. “We recently returned him to the exhibit with his family, where he’ll get a lot more exercise, and that will be the best thing to return to normal function of his leg,” she insists.

Whether that’s the best thing for his relationship with his mate remains to be seen. But for now, Ramone seems content to get back to the business of being a monkey—eating produce, interacting with fellow primates, entertaining the visitors, and “howling,” quite loudly.

Department:

Foster Hospital for Small Animals