-

About

- Leadership & Faculty

- News & Events

-

Academics

- Graduate

- Advanced Clinical Training

- Continuing Education

- Academic Departments

- Academic Offices

- Simulation Experiences

-

Student Life

- Offices

-

Research

-

Hospitals & Clinics

- Emergency Care

- Hospital Services

-

Community Outreach

- Volunteer

How IVF can be Used in the Conservation of Endangered Species

Danielle Sosnicki Chronicles her MCM’17 Summer Externship at the Colorado State University Department of Biomedical Sciences

When your day starts with an Igloo cooler full of ovaries, you know it’s going to be a good one. Fortunately, several days of my externship at the Animal Reproduction & Biotechnology Laboratory at Colorado State University started out this way, where most of my time was spent learning how to perform in vitro fertilization (IVF) using specimens from cows. As a student in the Master of Science in Conservation Medicine (MCM) program at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, I look forward to linking what I have learned about assisted reproductive technologies like IVF with how they can be used for conservation of endangered species.

The IVF Procedure

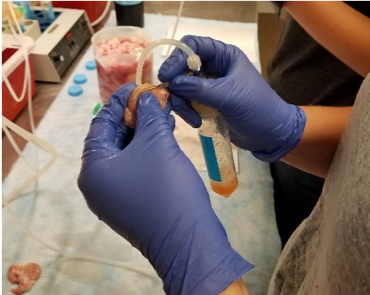

Ovaries from animals that were processed for meat were collected and set aside to be repurposed for the IVF process. Once back at the lab, we cleaned the ovaries and then the aspiration process began. This involved using a needle and some suction to collect any fluid and oocytes, or eggs, in the follicles that could then be used to carry out the IVF procedure. Once all the ovaries were aspirated—and sometimes we had almost 100 ovaries total—it was time to start searching for those eggs. I had lots of time to perfect my technique as this was the longest and most difficult part of the process, in my opinion.

Sperm being counted on hemocytometer.

Because the eggs that were harvested were immature and therefore not ready for fertilization, they had to incubate in maturation media overnight. Once mature, the oocytes were ready to be fertilized! We used frozen bull semen for this IVF procedure and performed a quick evaluation to determine sperm concentration by counting the number of sperm on a hemocytometer, a type of microscope slide that has a grid on the bottom to make counting easier and allows you to use a mathematical formula to determine the concentration.

Once the sperm preparation was completed, it was time for the magic to happen! A specific amount of sperm was added to the eggs and left in an incubator overnight. The next morning, we removed the fertilized eggs from the plates, and for the next several days we checked the embryos to determine how many cells they had divided into and ones that were progressing normally were allowed to continue to develop in fresh media. I am happy to report that even on my very first round of IVF I had living embryos at the end of the seven-day process and I continued to have success with each additional round I performed for the rest of my externship!

Bison Conservation

My externship mentor, Dr. Jennifer Barfield an assistant professor of reproductive physiology at CSU has successfully used assisted reproductive technologies to reintroduce pure bison (Bison bison) with Yellowstone genetics to the northern Colorado prairie at the Laramie Foothills Bison Conservation Herd. In addition to using IVF, artificial insemination and embryo transfer, she also used a washing procedure to clean the sperm and embryos of the bacteria that causes brucellosis. Brucellosis is a devastating zoonotic disease that can infect cattle causing abortions, infertility and lowered milk production, and can cause severe flu-like illness in humans. The disease is endemic to Yellowstone and because it has no treatment in animals, has made reintroducing Yellowstone bison to other parts of the country nearly impossible.

Assisted Reproductive Technologies as a Conservation Tool

Bison are not the only animals that can benefit from the use of assisted reproductive technologies and I have made this the primary focus of my case study, another course requirement in the MCM program. Many of the procedures have been developed for use in humans and domestic animals, but with a better understanding of the reproductive physiology of wild species and some tailoring of the procedures, they can be successfully used in other species. Conservation medicine is considered a crisis discipline and assisted reproductive technologies that are used to help critically endangered species are arguably the last chance these species have for survival. Advancing research in this field will allow these procedures to be applied to a wide variety of wild and endangered species. It’s important for conservationists to add these technologies to their toolboxes when working on solutions for endangered species, as it may be the only chance some of them have to avoid extinction.