-

About

- Leadership & Faculty

- News & Events

-

Academics

- Graduate

- Advanced Clinical Training

- Continuing Education

- Academic Departments

- Academic Offices

- Simulation Experiences

-

Student Life

- Offices

-

Research

-

Hospitals & Clinics

- Emergency Care

- Hospital Services

-

Community Outreach

- Volunteer

Equine Clinical Case Challenge: Intermittent Hematuria

History A 16-year-old pony gelding presented for evaluation of intermittent hematuria. The pony was reported to be previously healthy and exhibited a normal ...

History

A 16-year-old pony gelding presented for evaluation of intermittent hematuria. The pony was reported to be previously healthy and exhibited a normal appetite and water consumption at home. The hematuria was first noted several weeks ago and appeared to be worse after exercise.

Presentation

During the initial examination, the pony appeared to be in good general health with normal vital parameters. When placed in a stall the pony was urinated normally and was noted to have a normal appearance to his penis and prepuce. Other than mild over-conditioning (Body Condition Score 6/9) no other physical abnormalities were identified during the routine clinical examination.

What are your differential diagnoses?

A variety of conditions can result in the clinical manifestation of hematuria. Differentials include underlying kidney disease, neoplasia (of the kidney, bladder or urethra), urethral tears and uroliths (stones).

What diagnostics should be performed?

To determine the cause of the hematuria, one or more diagnostic procedures are typically required. Assessment of the kidneys as a source of the hematuria can include routine blood work (CBC and serum chemistry), urinalysis and ultrasound. Potential causes of hematuria would include the presence of stones, neoplasia, acute and chronic kidney injury.

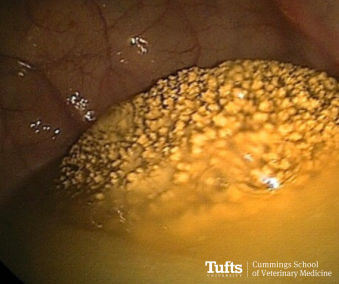

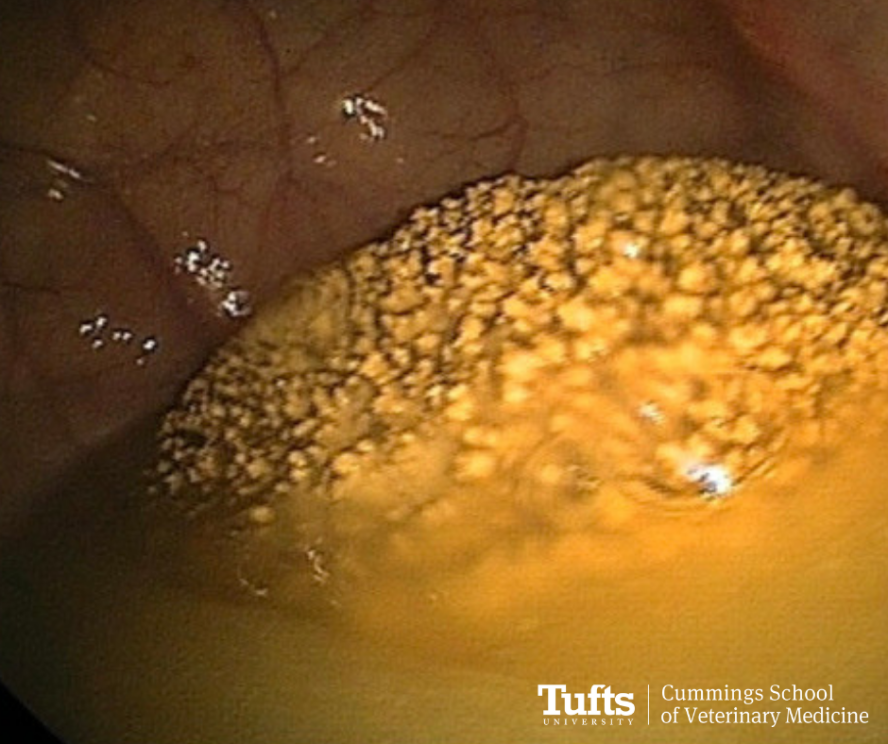

Cystoscopy of the patient in this case, with a large urolith seen partially immersed in a pool of urine.""

The bladder may be evaluated via palpation per rectum, transrectal ultrasound and cystoscopy. These diagnostics would allow for the identification of stones or tumors affecting the bladder and leading to the observed hematuria. Finally, the urethra is most readily evaluated endoscopically, although ultrasound may have value in some cases. Although the urethra is a less common source of blood, urethral tears can occur which result in hematuria which may be observed by the owner. In this case, palpation per rectum identified a stone in the bladder, which was confirmed via cystoscopy.

Routine blood work (CBC and serum chemistry) were unremarkable. Based on these findings what management strategy would you recommend?

Recommendations:

Several surgical procedures have been utilized to remove bladder stones in geldings including perineal urethrostomy, standing pararectal cystotomy and laparocystotomy under general anesthesia. The perineal urethrostomy can be performed standing with the intent to fragment and remove stones from the bladder. The procedure is typically more traumatic to the urethra and bladder than the alternatives. In addition, as the stone must be fragmented prior to removal, if any small fragments are left behind, they will serve as a nidus for the formation of new stones. This procedure if often best used for removal of solitary small stones which have passed into the urethra.

The standing pararectal cystotomy is also performed with the horse standing utilizing sedation, local anesthesia and typically an epidural. In this approach, a pararectal incision is made and blunt dissection is performed cranially to the neck of the bladder. One hand is placed in the rectum to position the stone into the neck of the bladder and the second hand is passed through the pararectal incision with a scalpel blade to incise over the stone. The stone is then removed and the incision is left to heal by second intention. Although generally well-tolerated, risks include injury to the adjacent rectum and septic peritonitis.

Laparocystotomy can be performed with the horse under general anesthesia. A modified parainguinal approach typically provide improved surgical access with less dissection required compared to a traditional ventral midline approach. As with the other techniques, direct visualization of the bladder is limited, but in cases when a single stone is present, this approach allows for easy removal of the cystolith.

In this case, due to the patient’s size, he was not considered a candidate for the pararectal cystotomy. Therefore, a laparocystotomy under general anesthesia was recommended.

Outcome:

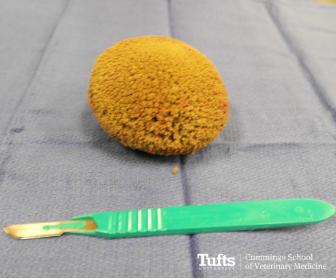

The cystolith was subsequently removed via a parainguinal laparoscystotomy under general anesthesia without complications. Incision into the bladder identifying the cystolith.

Discussion:

This mineral substrate is present in abundance in equine urine due to their diet. In most cases, the urine is culture negative for bacterial growth. Unlike in small animals, medical management has not historically been recognized as being successful for management of uroliths in horses. As a result, surgical removal is required to resolve the clinical signs. Unfortunately, due to the abundance of crystals in horse urine, recurrence is possible and reported in up to 41% of the cases. The surgical technique utilized for removal does appear to impact the risk of recurrence, with patients undergoing perineal urethrotomy at increased risk of recurrence. Although prevention through dietary modification or urine acidification has not been well studied in horses, the recommendation is typically made to avoid forages high in calcium (legumes) or additives to the diet which contain excess calcium. Additionally, encouraging increased water intake is recommended to dilute the solutes in the urine.

The Clinical Case Challenge from our General Surgery Service at Tufts Equine Center is led by board-certified surgeons and leaders in their field and renowned for their skills as well as the development of innovative procedures, techniques and advances in equine surgery. They specialize in soft tissue, orthopedic, respiratory and abdominal surgery and are committed to returning horses to peak performance and providing owners, veterinarians and trainers with exceptional service. We are fully equipped with state-of-the-art facilities and supported by our Anesthesia Service of experienced board-certified anesthesiologists and highly trained technicians. This winning combination allows us to carry out the latest and most advanced surgical procedures resulting in faster recovery times for your horse.

References:

Abuja GA, Garcia-Lopez JM, Doran R, et al. Pararectal cystotomy for urolith removal in 9 horses. Vet Surg. 2010; 39:654–659.

Laverty S, Pascoe JR, Ling GV, et al. Urolithiasis in 68 horses. J Vet Surg. 1992; 21:56–62.