-

About

- Leadership & Faculty

- News & Events

-

Admissions

-

Academics

- Graduate

- Advanced Clinical Training

- Continuing Education

- Academic Departments

- Academic Offices

- Simulation Experiences

-

Student Life

- Offices

-

Research

-

- Transformative Research

- Centers & Shared Resources

-

-

Hospitals & Clinics

- Emergency Care

- Hospital Services

-

Community Outreach

- Volunteer

Clinical Case Challenge: Cat with Recurrent Ear Infections

Novel treatment successfully cures Ragdoll cat with rare immune disease

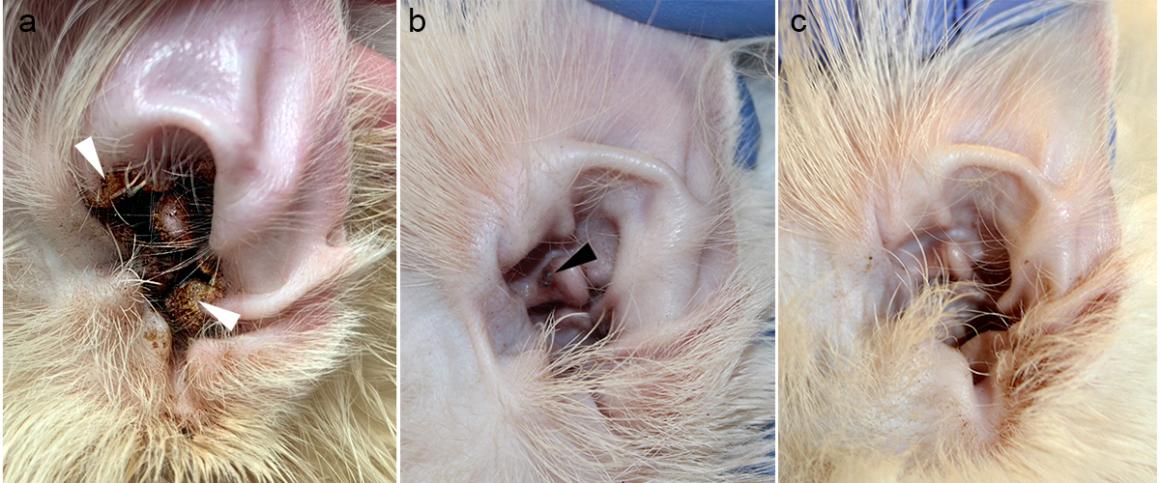

A six-month-old Ragdoll cat named Gaston presented at Henry and Lois Foster Hospital for Small Animals (FHSA) at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University, suffering from recurrent ear infections, crusts, and lesions on his ears.

History

Gaston was referred by his veterinarian to FHSA after three months of persistent ear infections. Topical and oral antibiotics had not resolved the infections. Gaston presented to the Dermatology Team at FHSA with dark brown adherent crusts and lesions in both external ear canals.

Can you solve this month's case?

Determine which diagnostics and treatments are required.\

The Dermatology Team started with a skin examination followed by microscopy of otic debris, which did not indicate ectoparasites. Cytological results showed cocci bacteria. Based on the symptoms of adherent crusty lesions in his ears and the diagnostic results, Gaston was diagnosed with feline proliferative and necrotizing otitis externa (PNOE), a rare immune-mediated condition, which in his case was complicated by a secondary bacterial infection.

Dr. Ekaterina Mendoza-Kuznetsova, assistant clinical professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences at Cummings School, explains, "With PNOE, the crust is very adherent, not possible to remove, and usually painful for the patient. If lesions obliterate the ear canals, the canals cannot function normally. Treatment is not always required, but this one was severe, chronic, and progressing."

In rare cases, patients with PNOE can also have extra-auricular dermatitis and middle ear involvement. Typically, immunosuppressive topical treatments resolve the condition.

The doctors picked up on a heart murmur and consulted with the Cardiology Team at FHSA. Gaston was also diagnosed with early-onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, unrelated to his PNOE.

Dr. Mendoza-Kuznetsova and Dr. Tim Chan, a dermatology resident in the Department of Clinical Sciences at Cummings School, recommended treating Gaston with an ear cleaner weekly and tacrolimus, a topical immunomodulatory ointment daily. Tacrolimus ointment is the most effective treatment for PNOE, according to the literature. They also prescribed a topical medication with selamectin to rule out ear mites.

At Gaston's follow-up appointment six months later, he showed complete remission of lesions in his left ear and partial remission in the right ear, with some crusts remaining in the right ear. The team stopped treating the left ear and continued with a tacrolimus every other day for the right ear. The right side improved within six weeks, but PNOE relapsed in his left ear. The cat restarted tacrolimus daily in the left ear.

Gaston's symptoms did not improve over the next few months despite a continuous course of the ointment. The team flushed his ear, removing as much material as possible. Though not typical, the team was concerned that the condition may have progressed into his middle ear, so they conducted a CT scan and biopsy, confirming their suspicion.

Because the lesions were now much deeper in the ear canal, they could not be addressed topically and needed a systemic treatment. The doctors prescribed an oral immunomodulatory medication, cyclosporine, which has a mechanism of action similar to the tacrolimus. The lesions in the left ear progressed over the next several weeks, so cyclosporine was discontinued. Because of the cat's heart condition, steroids were not a treatment option. The team decided on surgery, a total ear canal ablation, and bulla osteotomy. Gaston's cardiologist recommended surgery sooner rather than later because the risk of anesthesia due to his heart disease would increase the longer they waited. With the condition still progressing with medication, they scheduled surgery a month out.

In the meantime, the Dermatology Team decided to try another option with oclacitinib, an active ingredient in a medication typically prescribed to treat allergies in dogs. Based on its mechanism of action and the known mechanism of PNOE, this medication was a good candidate for a trial. The Dermatology Team decided to trial oclacitinib therapy.

"Oclacitinib had not been used with PNOE, but showed some efficacy with diseases similar to this condition. While waiting for surgery, we decided to try this medication," said Dr. Mendoza-Kuznetsova. "He responded to treatment surprisingly quickly, even faster than working with standard treatments. In two weeks, we saw great improvement. The lesions almost completely resolved in one month, so we canceled the surgery."

Three months later, Gaston returned to FHSA in almost complete remission, with only a small adherent crust in the left ear. The doctors discontinued the tacrolimus but kept him on the oclacitinib, gradually tapering the dosage.

A recent ultrasound of his middle ears and otoscopy showed the PNOE had completely resolved, with no lesions. Gaston is now on no medications and in complete remission. Fortunately, though unrelated to his PNOE, his heart disease had also stopped progressing.

"The cat was on the oclacitinib for more than a year and half with no side effects," says Dr. Mendoza-Kuznetsova. "It's an option that's safe and effective."

This is the first known case of treating PNOE with this oclacitinib. Drs. Mendoza and Chan recently published a case study detailing the trial.

Comments from Cummings School's Dermatology Team

"This is a truly rare disease," says Dr. Mendoza-Kuznetsova, noting that only a few cases have been published about cats with PNOE. She has seen less than half a dozen in her career, and Gaston is Dr. Chan's first case in his three years in dermatology.

While PNOE is known to dermatologists, Dr. Mendoza-Kuznetsova explains that she would not expect a general practitioner to recognize it because of how uncommon it is and also notes that PNOE in the middle ear can only be detected by CT scan or MRI. "If a vet sees any skin or ear infections not resolving with appropriate treatment, it usually means an underlying disease is not being addressed, and the vet should think about referring the patient. We appreciate that the local vet referred the case to us after two or three months of treatment, so it was not too late. The clinical presentation and good previous diagnostic workup by the vet helped us to rule out some conditions and focus on the most likely diagnosis."

PNOE often resolves itself without treatment. Dr. Chan adds, "If a vet suspects a disease like this, they should try typical treatments first. This is an alternative if those are not working. When PNOE is more severe and topical treatment alone is not resolving it, alternatives for systemic treatment should be considered. Oclacitinib is a relatively safe option for systemic treatment."

This marks the first successful treatment of feline PNOE with oclacitinib therapy.

Department:

Foster Hospital for Small Animals