-

About

- Leadership & Faculty

- News & Events

-

Admissions

-

Academics

- Graduate

- Advanced Clinical Training

- Continuing Education

- Academic Departments

- Academic Offices

- Simulation Experiences

-

Student Life

- Offices

-

Research

-

- Transformative Research

- Centers & Shared Resources

-

-

Hospitals & Clinics

- Emergency Care

- Hospital Services

-

Community Outreach

- Volunteer

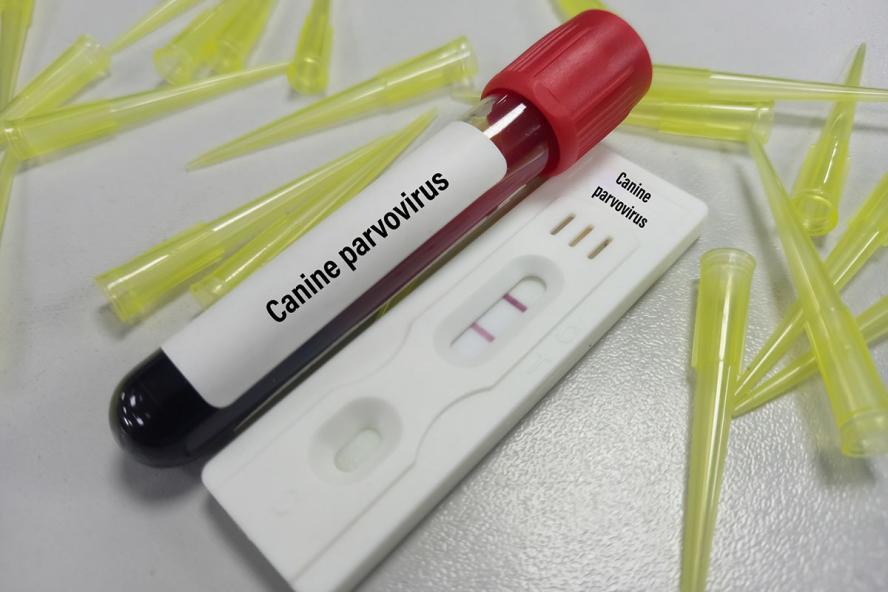

Canine Parvovirus

Five Things to Know

An outbreak of parvovirus in northern Michigan this summer led to the loss of life for more than 30 dogs. Here are five things to know about canine parvovirus.

Causes and Protection

Parvovirus, or “parvo,” is a viral disease, transmitted primarily from one dog to another through contact with contaminated feces. Blood-borne infections occur occasionally as well, such as in-utero from a pregnant female to dog to her puppies in late pregnancy or soon after birth. Parvo is preventable, and dogs are routinely vaccinated starting at eight weeks of age. Parvo vaccines in the U.S. are usually given as a core vaccine (DAPP – covering distemper, hepatitis, parvovirus, and parainfluenza). Occasionally we see young dogs who are not fully vaccinated develop parvo because multiple booster vaccines are necessary to confer full protection/immunization. (This occurred with several cases in Michigan.)

Can a vaccinated dog still contract it?

Infections in dogs outside of puppyhood (6–12 months of age) are exceedingly rare, likely because of the beneficial effect of vaccination. However, as mentioned earlier, multiple doses of the vaccine are needed to booster adequate immunity to avoid infection, partially vaccinated dogs can contract parvo. For this reason, we commonly test young dogs for parvo when they come to the ER for signs of GI upset, even if vaccines have been given. Parvovirus is unfortunately very hearty in the environment and is relatively contagious from one dog to another, so parvo testing is a helpful infection control measure to avoid bringing affected dogs physically into the ER near other potentially susceptible dogs.

Watch for symptoms in your dog

Parvovirus affects numerous different areas/organs in the body, but primarily infects cells with a high rate of replication. Most commonly, the primary problems we see are gastrointestinal and bone marrow issues. Rarely, we can see neurologic symptoms as well. The most common symptoms include lack of appetite, diarrhea, vomiting or regurgitation, depression, fever, and low white blood cell count. The virus causes substantial damage to the inside lining of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, to which many of the signs can be attributed. Dogs affected with parvo are also at risk of secondary bacterial infections due to the often-substantial GI tract damage coupled with low white blood cells, rendering them immunocompromised to avoid such secondary/opportunistic infections.

Treatment options

The treatment for parvo is largely supportive/symptomatic. Most dogs require hospitalization for IV fluid therapy due to mild to severe dehydration from diarrhea, vomiting, and reluctance to eat/drink. Often prophylactic antibiotic therapy is given due to the compromise of the GI tract and concern for secondary infections. In addition, many dogs develop leukopenia (low white blood cells), making it far more difficult to fight off secondary bacterial infection, which is another good reason to give prophylactic antibiotics. It should be noted that antibiotics kill bacteria, but not viruses such as parvovirus. Dogs with more critical infections often require temporary feeding tubes or blood transfusions, but this is decided on a case-by-case basis.

Is parvovirus a life-threatening illness?

With appropriate veterinary care, most dogs make a full recovery. However, despite every possible intervention, we do sometimes see severely affected dogs die from parvo, which is why we take it very seriously. Previous studies have shown a survival rate above 90 percent with veterinary care. There is some concern that over time, the types of strains we see of parvo in dogs have evolved to cause more severe disease, but this has not necessarily been proven with research. The most important thing to know is that if you own a very young dog (especially less than three months of age) who is having signs of GI upset, prompt medical attention should be sought.

Dr. Ian DeStefano (he/him/his) is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences at Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts University. He serves as co-chair of the Henry and Lois Foster Hospital for Small Animals’ Infection Control and Antimicrobial Stewardship Team.

Department:

Foster Hospital for Small Animals