-

About

- Leadership & Faculty

- News & Events

-

Admissions

-

Academics

- Graduate

- Advanced Clinical Training

- Continuing Education

- Academic Departments

- Academic Offices

- Simulation Experiences

-

Student Life

- Offices

-

Research

-

- Transformative Research

- Centers & Shared Resources

-

-

Hospitals & Clinics

- Emergency Care

- Hospital Services

-

Community Outreach

- Volunteer

Clinical Case Challenge: More than Blepharospasm OS

HISTORY: A 21-year-old Standardbred mare presented for a three- week history of discharge and blepharospasm OS. Previous treatment included topical triple ...

HISTORY: A 21-year-old Standardbred mare presented for a three- week history of discharge and blepharospasm OS. Previous treatment included topical triple antibiotic ointment and systemic minocycline with no improvement. The mare was previously healthy with no history of ocular issues. There was no history of trauma to the eye. The owner reported that the mare is uncooperative for administration of topical medications.

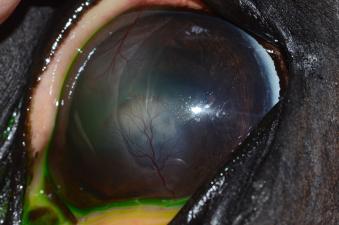

On examination at Tufts Equine Center the mare was visual in both eyes. The pupil was miotic in the left eye with a decreased direct pupillary light reflex. There was flare present in the left eye, and a focal cream-colored opacity was noted in the ventral cornea (figure 1). It appeared to involve deeper portions of the cornea. The overlying cornea was clear, no neovascularization was noted, and the corneal surface did not retain fluorescein stain. Intraocular pressure was 12 mmHg. The right eye was considered normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT PLAN?

Flare and miosis are consistent with uveitis. Uveitis in horses may be caused by any number of things. Before instituting a systemic workup to look for underlying causes, however, the equine practitioner must first rule out the presence of other ocular issues that may trigger uveitis, particularly corneal ulcers and corneal stromal abscesses.

In the case of this mare, the deep corneal opacity is a critical finding. This opacity is most consistent with a corneal stromal abscess (SA). Stromal abscesses in horses are most commonly fungal in origin, although they can also be bacterial or sterile. They are believed to result from a microscopic corneal trauma that inoculates organisms into the deeper layers of the cornea. The epithelium either sustains minimal damage or is able to cover the microscopic defect rapidly. Because of their location, obtaining samples from SAs for cytology or culture is complicated and is rarely done.

SAs may trigger intense uveitis. In some horses, the SA may be difficult to visualize against a background of corneal edema, heavy flare, and/or hypopyon. Because a finding of corneal disease markedly alters the treatment regimen, it is critical to inspect the cornea carefully whenever uveitis is diagnosed in a horse. Treating a horse with uveitis with topical steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs would be appropriate in the absence of corneal disease. In a horse with a SA, however, use of these topical medications can be disastrous to the cornea and may even worsen the uveitis.

Horses with SAs are often quite uncomfortable and difficult to medicate. Placement of a subpalpebral lavage system (SPL) allows the owner to medicate the horse safely and ensures that medication reaches the ocular surface. In the case of this mare, an SPL was placed in the lower eyelid. She was started on voriconazole and ofloxacin (both 4 times a day) and atropine (twice a day until pupil dilated, then decreased to once a day). Voriconazole, an azole antifungal, and ofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone antibiotic, were chosen for their superior ability to penetrate an intact corneal epithelium. Banamine (flunixin meglumine) was to be administered orally, and oral minocycline was continued for its anti-inflammatory properties.

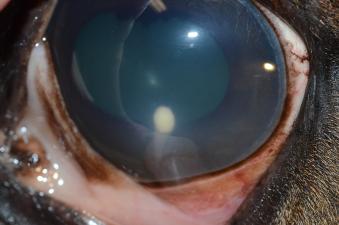

The owner was advised of the challenges in treating SAs. Effective medication delivery to the posterior cornea is a challenge. SAs may resolve with medical management if neovascularization progressing from the limbus reaches the lesion (figure 2 shows a different horse, with a SA treated successfully with traditional medical management). This is a slow process and pain or complications from uveitis may force more significant intervention. Some horses with SAs require enucleation due to complications or owner finances. A recheck was planned for this mare for the following week.

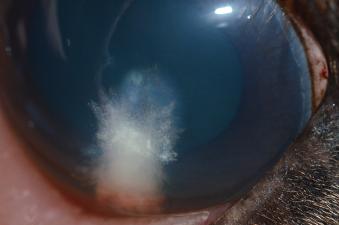

At the time of recheck, the owner reported that the mare seemed more comfortable and that medication administration had been straightforward with the SPL in place. The pupil was moderately dilated, and neovascularization could be seen progressing from the dorsal and ventral limbus. No flare was present. Intraocular pressure was again 12 mmHg. The SA, however, was significantly larger (figure 3;the curved line to the left is the reflection of the photographer’s hand on the cornea).

WHAT ARE YOUR OPTIONS?

The SA in this horse appears to be enlarging despite treatment, although the uveitis has improved. At this stage there are 4 options:

- Continued medical management despite SA progression and limited neovascularization

- Intrastromal injection of voriconazole

- Surgical removal of the abscess coupled with placement of grafting material

- Enucleation

Continued medical management alone would have kept this mare out of work for months, and the owner wished to preserve the eye, taking enucleation off the table. Intrastromal injection, one of the two remaining options, involves using a 27g needle to inject voriconazole within the layers of the cornea, as close as possible to the SA. This procedure has been shown to be effective in inducing resolution of SAs and has a favorable safety profile when performed by a trained ophthalmologist. It requires heavy sedation but not general anesthesia. The best surgical option for this mare’s SA, on the other hand, would have been a posterior lamellar keratoplasty (PLK). This technique involves creation of a flap in the unaffected cornea overlying the SA. The SA is then excised, and a button of donor cornea or other material is sutured into the defect. The corneal flap is then repositioned and sutured. This procedure has a high success rate but must be performed by an ophthalmologist and must be done under general anesthesia with the aid of an operating microscope.

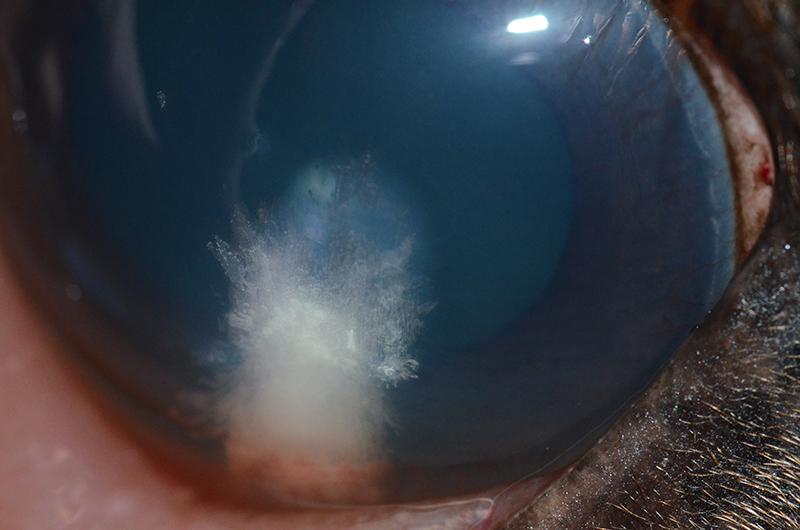

The owner elected intrastromal voriconazole injection, with a plan to proceed to PLK if results were unsatisfactory. The mare was heavily sedated and 25 mg (0.5 mL) of 5% voriconazole was injected into the cornea overlying and surrounding the SA. An expected sequel to this procedure is corneal stromal fracture, or separation of the corneal lamellae as material is injected. Stromal fracture has a “cracked glass” appearance and can appear quite dramatic (figure 4) but generally resolves within 24 hours (figure 5). Corneal rupture is a potential adverse outcome of this procedure but can be avoided with proper sedation, proper equipment, and proper training.

This mare was rechecked by the referring veterinarian and the SA was reported to decrease in size over the course of the following five weeks. Topical medication was discontinued by the referring veterinarian at the end of that time and the SPL was removed. Minor fibrosis remains at the SA site but the horse is visual and comfortable with no sign of recurrence.

It is important to note that intrastromal voriconazole injection tends to lead to regression of neovascularization and healing without neovascularization present. This can be disconcerting, as neovascularization is needed for resolution of SAs with traditional medical management but seems to be part of the healing process for horses who have undergone this procedure.

Dr. Stephanie Pumphrey from our Ophthalmology Service treats a wide range of equine ocular diseases. Her primary interest is in nonsurgical alternatives for the treatment of corneal ulcers and abscesses. She regularly performs a variety of ocular surgeries in horses, including tumor removals, grafts for corneal ulcers and cyclosporine implants for equine recurrent uveitis. Dr. Pumphrey earned her D.V.M. from Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts. She went on to complete her ophthalmology residency at Cummings School in 2012 and became board-certified the same year. Dr. Pumphrey took a less traditional route to her D.V.M., completing a Ph.D. in American Literature prior to applying to veterinary school. While a Ph.D. student, she got her first dog, and in spending time with her local veterinarian she realized that veterinary medicine was a better fit for her skills and interests than the humanities. During veterinary school, she completed several rotations on the ophthalmology service and was attracted to the discipline for its combination of medicine and surgery, and for its obvious impact on the quality of life of its patients.