“ARDS is fairly uncommon but very serious because it can carry a mortality rate above 70 percent,” says Dr. Daniela Bedenice, professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences and specialist in Emergency and Critical Care (ECC) and Internal Medicine at HLA. “This cria had a plethora of different medical problems, but the most serious were related to the respiratory tract.”

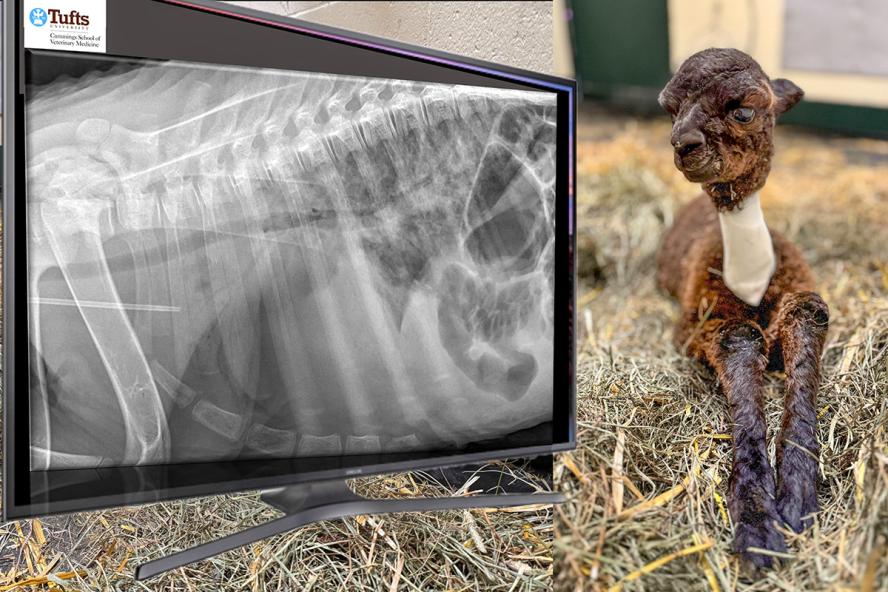

The doctors administered conventional oxygen to Griffin through a nasal tube, but his blood oxygen levels remained low, and radiographic imaging showed severe abnormalities in his lungs. He also showed evidence of sepsis, which refers to a form of body-wide infection, in addition to acute kidney injury.

“This cria was so unwell that every decision had to be carefully thought through so that we would not lose him,” says Dixon. “Dr. Lehmann was woken up every night with techs calling to ask questions. “Those first few days, we didn’t know if the cria would make it.”

In patients who do not respond to conventional oxygen therapy, the next step typically would be to anesthetize the alpaca for machine ventilation to deliver oxygen. However, machine ventilation is invasive, not without risk for animals, and often cost-prohibitive for owners. Since Griffin was about the size of a cat, the clinicians reached out to the ECC team at FHSA to improve his ventilation non-invasively.

A newer method for treating respiratory failure, high-flow nasal oxygen therapy, is often used for dogs in the intensive care unit at FHSA before reaching for mechanical ventilation. To date, it’s only rarely been applied to large animals. In this system, oxygen flows through nasal tubes, called “prongs,” at a high rate to open the airways.

“High-flow oxygen can help the animal breathe better and deeper and get more oxygen on board,” says Dixon. “The nasal prongs fit perfectly for the cria, and it was the first time we successfully used prolonged high-flow oxygen therapy in a cria in this situation.”

Dr. Alexia Berg, on the ECC team at FHSA and assistant clinical professor in the Department of Clinical Sciences, explains that patients receiving this therapy can be awake and even walk around during treatment. “For the right patient and the right problem, it can make the difference between making it out of the hospital or not,” she says.

Berg provided her expertise in using the equipment and lent it to HLA so that the alpaca could be with his mother. After five days of high-flow oxygen therapy, Griffin finally turned the corner.

“Having this therapy as an option was the reason this cria lived,” says Dixon. “It’s great to have so much expertise in the same building. All the teamwork, brainstorming, and experience certainly paid off and made a difference for this little guy.”

“We’re thrilled it worked for them,” says Berg. “We’re glad we could offer the technology, that they were open to trying it, and it worked great for him.”

Karen Nace appreciated the large and small animal teams working so closely to help save the cria.

“I don’t think he would have survived if it weren’t for the collaboration between all the vets at the hospitals,” she says. “They really did an amazing job with him. They were absolutely wonderful and very communicative.”

Griffin underwent intensive care, and as his condition improved and he was able to stand, the team turned their attention to nursing.

“For him to learn what a healthy cria would normally achieve in the first two hours after birth took a week,” says Dixon. “It’s exciting when they finally latch on, independently suckle, and no longer want the bottle. The dam was amazing, fantastic to handle, and good with him. She made it a lot easier.”

Bedenice spreads the credit around for the cria’s remarkable recovery. “The owner and attending vet referred the animal early, which was a key factor for survival. This was a unique scenario where we had the opportunity to identify the disease early and initiate a newer way of treatment immediately after normal oxygen support failed. Another reason this animal did well is that alpacas are genetically adapted to tolerate low oxygen environments since they are a high-altitude-adapted species. The strong collaboration between many clinicians and staff involved in the cria’s care was absolutely essential for his recovery. It’s professionally rewarding to put our minds together and optimize care of patients large and small, and it’s fun too.”

Griffin is back home with Best Lady at Crimson Skye Farm, now fully recovered, aside from some scarring in his lung tissues that should not impact his breathing, and he’s up over 20 pounds. In finding a name for the cria, Karen Nace looked up “warrior” and “survivor” and found a fit with “Griffin.”