Heart Disease - Dogs

Heart Disease Resources: Basics | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Dogs | Cats | Treatments | Medications | Nutrition | Forms

The heart is an important and complex organ, and heart disease in dogs can show up in a variety of ways affecting specific parts of the heart and body.

Some heart conditions are present at birth (called congenital heart defects). The most common congenital heart defects in dogs are patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), subaortic stenosis (SAS), pulmonic stenosis, and ventricular septal defect (VSD).

Other heart conditions develop as the dog ages. Some of the most common heart conditions in dogs are degenerative mitral valve disease, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), and pericardial disease.

Another condition affecting the heart is heartworm disease. Heartworms are transmitted by mosquitos and can affect cats and dogs. This disease is more common in certain parts of the world, especially in warmer regions.

The information included in this section covers the most commonly diagnosed heart diseases in dogs. However, because every dog is unique, your dog may not show the typical symptoms, or your dog may have a less common disease that is not listed here. Diagnosis and treatment will be specific for your dog. Your veterinarian can answer specific questions you have about your dog’s condition.

-

Overview

Mitral valve disease is the most common heart disease in dogs. It results from a thickening of the mitral valve as a dog ages. Because the mitral valve is the gate between the two left heart chambers, it leaks blood and the heart enlarges. Mitral valve disease can progress to congestive heart failure (CHF).

The condition goes by many names including myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD), degenerative mitral valve disease (DMVD), chronic valvular heart disease, or just “mitral regurgitation”.

Symptoms

Small-breed dogs of middle to older age are most commonly diagnosed with mitral valve disease, although large-breed dogs can also develop the disease. Common breeds include the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, Dachshund, Cocker Spaniel, miniature and toy Poodle, Shih Tzu, Lhasa Apso, Maltese, Chihuahua, and many other small to medium size dog breeds. Nearly all Cavalier King Charles Spaniels will eventually develop mitral valve disease.

Mitral valve disease is a slowly progressive disease that your veterinarian may diagnose before there are any symptoms. Your veterinarian may suspect mitral valve disease based on listening to the heart with a stethoscope and finding a new heart murmur.

Listen to a dog's normal heart sounds here.

Listen to a normal heart murmur from a dog with mitral valve disease here.

Excessive coughing, difficulty breathing, and fainting all can be emergencies that may require urgent veterinary care.

Diagnosis & Testing

As part of the diagnosis for mitral valve disease, your veterinarian will begin with a complete physical examination. In addition to listening to your dog’s heart murmur, your veterinarian may hear other abnormalities such as an arrhythmia or a mid-systolic click (see below). They will also note the breathing rate and effort, listen for abnormal lung sounds, and check the color of the gums (they should be pink!).

Listen here to a mid-systolic click in a dog's heart.

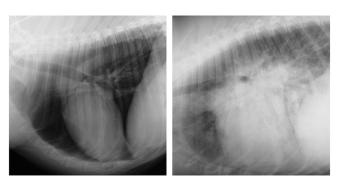

Your veterinarian may recommend chest radiographs (x-rays) to look for an enlarged heart or to search for evidence of fluid buildup in the lungs (congestive heart failure).

An electrocardiogram (ECG) may also be recommended to look for evidence of irregular heartbeats, also called cardiac arrhythmias.

Further testing may include an echocardiogram (echo). Echoes are best completed by a veterinary cardiologist or someone with similar advanced training in cardiology. An echo will allow the veterinarian to see the thickening of the mitral valve, evaluate the amount of blood leaking through the mitral valve with each heartbeat, and measure the degree of enlargement of the heart. The echo will help your veterinarian determine the severity of your dog’s mitral valve disease and determine the best approach to disease management. For information on finding a veterinary cardiologist to perform an echo, visit the Find Vet Specialists website.

Your veterinarian may also recommend bloodwork and a urine test to ensure your dog is healthy enough for medications. A special blood test to check for a substance called NT-proBNP (or sometimes just called BNP) may help your veterinarian determine the severity of your dog’s mitral valve disease.

Visit our Diagnosis page for more information.

Treatment

Treatment of mitral valve disease is in part based on the severity of the disease. There is a consensus statement from a committee of veterinary cardiologists on how mitral valve disease should be diagnosed and managed, and this paper is available for free from the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. There is no treatment designed to reverse the aging changes of the mitral valve, but medications and diet changes are often used to manage mitral valve disease. As the disease gets more advanced, more medications are used.

In the very early stages of mitral valve disease, when there is minimal heart enlargement and the murmur is soft, no drugs are indicated, although some diet changes might be considered, especially in dogs that are overweight or too thin.

As the leak at the mitral valve gets worse, and the murmur gets louder, your veterinarian will recommend testing such as chest x-rays, an echo, or BNP testing.

If the heart is moderately enlarged, even if your dog does not have any symptoms, your veterinarian may recommend a drug called pimobendan. Pimobendan has been shown to delay the onset of congestive heart failure in dogs with mitral valve disease by up to 15 months in the typical dog. Your veterinarian may recommend other drugs if the heart disease gets worse or if your dog has elevated blood pressure.

Once your dog begins showing symptoms of heart disease, such as cough, difficulty breathing, or fainting, your veterinarian may recommend additional testing.

If the chest x-rays confirm fluid buildup in the lungs (congestive heart failure) treatment usually includes pimobendan plus several additional medications. Furosemide (also called Lasix or Salix) is a diuretic, or “water pill”, used to clear the fluid that is retained in the lungs or elsewhere in the body. The dose of furosemide is often adjusted over time, and if you can monitor your dog’s breathing rate and effort then this can help in adjustment of the diuretic dose. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (e.g., enalapril, benazepril, or lisinopril) are used to help prevent the fluid from coming back. Spironolactone, another type of diuretic, can also be helpful at this stage of heart disease. Other heart medications can be added as the disease progresses.

Surgery on the mitral valve might also be an option for some dogs, however, the surgery is difficult, very expensive, and only available at a few sites worldwide.

If your pet has advanced mitral valve disease, your veterinarian will likely recommend limiting your dog’s exercise to minimize the heart’s workload.

A low-salt or low-sodium diet is usually recommended for dogs with mitral valve disease, although the degree of sodium restriction depends on the severity of your dog’s disease. For a list of low-salt diets, omega-3 fatty acids, and other nutritional issues that are important for pets with heart disease, please see our Nutrition page.

Your veterinarian may also ask you to help track your pet’s health at home. This could be recording your pet’s breathing rate and breathing effort or noting medication administration times. Use our tracking sheets to help record this information.

Long-term Care & Outcomes

Dogs with mitral valve disease will need frequent rechecks to make sure the disease is being optimally managed. This includes ensuring medications are not causing undesirable side effects and, most importantly, that your dog’s quality of life is maintained. Serial blood tests (often done every 2-6 months) are done to check kidney values and electrolytes since alterations can cause dogs to feel weak or lose their appetite. Recheck chest x-rays may be needed to search for return of fluid in the lungs. A recheck echo may help determine the need for additional medications.

Mitral valve disease can be slowly progressive in some dogs. Not all dogs with mitral valve disease will develop heart failure. And some dogs with mitral valve disease will live a normal lifespan.

Once symptoms of heart failure have developed (cough, difficulty breathing, fainting), many dogs can live for 6 to 12 months with heart medications and changes to diet and lifestyle. A much smaller proportion of dogs will live 18 months or longer with careful treatment.

In most dogs, the disease progresses, and one or more complication develops. Some dogs have heart failure that worsens and will no longer respond to drug therapy (refractory heart failure). Some dogs can be on 8 or more medications before they stop responding to treatment. In other dogs, kidney failure develops and causes loss of appetite, although adjustment of heart medications can restore kidney function in some dogs. Other dogs may die suddenly and without warning. Finally, some dogs struggle with the quality of their life and the difficult decision for euthanasia is made.

Your dog’s individual prognosis depends upon many factors and your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist will be better able to discuss what you can expect for your dog. -

Overview

Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is the second most common canine heart disease. It is the most common heart disease in large breed dogs. In DCM, the heart chambers become dilated, while the heart walls (heart muscle) thins. These thinner heart walls are weaker and cannot perform the normal workload expected of the heart. They contract weakly and do not push blood forward to the rest of the body. Congestive heart failure commonly develops in dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy.

The cause of DCM is not known in many cases. However, genetic forms of the disease exist. Breeds like the Golden Retriever and Cocker Spaniel may develop DCM due, in part, to a taurine deficiency. Some cases of DCM are now being linked more generally to certain types of dog foods. This form of the condition is called nutrition- or diet-associated DCM.

Symptoms

Giant and large breed dogs of middle to older age are predisposed to develop DCM. Commonly affected breeds include the Scottish Deerhound, Irish Wolfhound, Great Dane, Saint Bernard, Afghan, Newfoundland, and Portuguese Water Dogs. There is a very high incidence of DCM in both Doberman Pinschers and Boxers, and these breeds can inherit a genetic form of DCM.

Some dogs may show no symptoms of DCM in the early stages of the disease. As the heart becomes more enlarged, your dog may appear weak or may want to exercise less. Other symptoms of DCM include difficulty breathing, coughing, weight loss, and fainting.

Excessive coughing, difficulty breathing, and fainting all can be emergencies that may require urgent veterinary care.

Diagnosis & Testing

Diagnosis of DCM may be suspected by your veterinarian based on the physical examination of your dog and careful listening to the heart (auscultation). Especially early in the disease, your dog’s physical exam may be completely normal. Other dogs with DCM have heart murmurs or arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms) that are detected on physical exam. Your veterinarian may also hear abnormal lung sounds that are a result of fluid buildup in or around the lungs. Based on what your veterinarian learns from the physical exam, he or she will recommend further testing.

If your veterinarian detects an arrhythmia, one of the next steps is an ECG. An ECG helps characterize the abnormal heart rhythm and helps determine whether drug treatment for the irregular heart rhythm is needed. Specific arrhythmias, like atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachycardia, are common in dogs with DCM and might require treatment. Since some arrhythmias can come and go, in some cases it is desirable to know what is happening with an ECG throughout the entire day, and in these cases, a Holter monitor recording might be recommended.

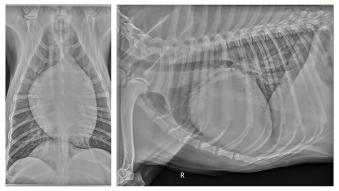

Chest x-rays may be recommended, especially if your dog has a cough or difficulty breathing. Depending on the stage of your dog’s DCM, chest x-rays may be normal, or only show mild heart enlargement.

If the disease is more advanced, your dog may have signs of congestive heart failure as fluid starts to build up in the lungs.

The echocardiogram (echo) is the gold standard for the diagnosis of DCM. Your veterinarian can see the enlargement of the heart chambers and the thinning of the heart walls. The echo also measures something called fractional shortening and the ejection fraction. These evaluate the ability of the heart to contract and pump blood. They are typically decreased in DCM, especially in dogs with heart failure.

Routine bloodwork may be recommended to rule out other conditions and to ensure your pet is healthy enough for medication. Specific blood tests may also be indicated. Your veterinarian may want to test your dog’s blood taurine levels or give taurine in case your dog has a deficiency of this nutrient. Levels of a substance called BNP (NT-proBNP or c-BNP) can be measured in the blood and will rise as the heart stretches. It can be useful to search for early disease or to determine whether difficulty breathing is likely due to heart failure. BNP is sometimes used to track the progression of DCM.

If your dog is a Doberman Pinscher or a Boxer, genetic testing is available to determine if your dog is at increased risk for developing DCM.

Treatment

Treatment of DCM depends on the stage of the disease. Some dogs may be diagnosed before symptoms are noticed, and this is sometimes called “occult DCM”. Treatment at this stage might include drugs to control cardiac arrhythmias, or drugs to try and delay the onset of heart failure such as pimobendan or ACE inhibitors.

Once congestive heart failure is present, medications that are commonly prescribed include furosemide or other diuretics, pimobendan, and an ACE inhibitor. Other medications will be added as the disease progresses or as your pet’s condition worsens. The dose of furosemide is often adjusted over time, and if you can monitor your dog’s breathing rate and effort then this can help in adjustment of the diuretic dose.

A low-sodium diet and specific nutritional supplements may be recommended. For more information on diet-associated DCM, please go to our Nutrition page.

Long-term Care & Prognosis

Your dog will likely require frequent veterinary visits to best manage their heart disease. Follow-up testing may be necessary. This may include repeat x-rays to check for more fluid in the lungs, bloodwork to check kidney function and electrolytes, recheck ECG or Holter to evaluate control of cardiac arrhythmia, or a recheck echo. As your dog’s heart condition worsens, additional medications may be necessary. Read our tips on giving medications to pets.

Your dog’s activity level should also be monitored and limited if it has heart failure. If your dog is having trouble breathing or falls behind while on walks, this is too much activity. Do not push your dog to exercise beyond their ability. Too much exertion puts additional stress on an already failing heart and could cause fainting or sudden death.

Unfortunately, in most cases, DCM is not reversible. The goal of treatment is to manage your dog’s symptoms and maintain your dog’s quality of life. Most dogs with DCM live for 2 to 12 months after the diagnosis of heart failure with the help of medications and diet. In many cases we suggest that survival for 6 months after the onset of heart failure is a good outcome, and survival past one year is terrific. The exception is diet-associated DCM which, in some cases, can be significantly improved with diet change and medication.

-

Overview

Pericardial disease refers to conditions affecting the pericardium, the thin sac that surrounds the heart. In a normal dog, this sac contains a small amount of fluid to help with lubrication of the heart while it is beating. In pericardial disease, this sac can become filled with fluid (called pericardial effusion). If enough fluid accumulates, the pericardial sac becomes too full and limits the return of blood to the heart, hindering normal heart function.

Pericardial diseases often develop in response to cancer or inflammation around the heart. One of the more common causes of pericardial effusion is a cancer that develops on the heart called hemangiosarcoma. Hemangiosarcoma often grows from the right atrium of the heart. This tumor causes bleeding into the pericardial sac.

Another type of cancer that can cause pericardial effusion is chemodectoma. It is a tumor that grows from the top of the heart near the aorta.

Fluid can also accumulate in the pericardial sac due to inflammation with resulting scar formation on the pericardial sac. When no clear cause for this inflammation or scarring can be found it is called idiopathic pericardial effusion.

Other cancers are known to cause pericardial effusion, and birth defects of the pericardial sac can also limit normal function of the heart.

Pericardial diseases are often not detected until they are an emergency.

Symptoms & Signs

Medium to large breed dogs, especially middle age or older dogs, are most prone to developing pericardial effusion. The most common breeds are German Shepherd dogs, Golden Retrievers, Labrador Retrievers, and Rottweilers. Certain breeds of dogs are likely to get a specific tumor type called chemodectoma that can cause pericardial effusion. This cancer is more common in short-nosed dogs like Bulldogs, French Bulldogs, and Boston Terriers.

Symptoms you may notice in your dog with pericardial effusion include a fainting episode or sudden collapse. Dogs with pericardial effusion can also exhibit difficulty breathing. They may a have bloated-looking stomach due to fluid buildup in the belly, called ascites.

Pericardial effusion is an emergency, and your pet should be evaluated right away if they have collapsed or are having trouble breathing.

Diagnosis & Testing

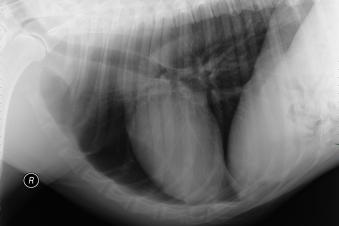

Diagnosis for any condition begins with a complete physical exam. Pericardial effusion can make it difficult for your veterinarian to hear the heartbeat, resulting in your veterinarian hearing muffled heart sounds. Your dog may also have a fast heart rate. When looking at your pet’s gums, your veterinarian may note a “muddy” or pale color instead of a normal pink color. A chest x-ray often reveals an enlarged heart with a round shape.

An echocardiogram (echo) is the best test to confirm that pericardial effusion is present. The echo can often help determine the cause of the fluid accumulation. Often a clear mass can be seen on either the right atrium (hemangiosarcoma) or at the top of the heart (chemodectoma). Sometimes the echo fails to find a clear mass. In these cases, the fluid buildup may be due to inflammation, infection, or other types of cancer.

Treatment

Pericardial effusion is often life-threatening. To immediately relieve the fluid buildup around the heart, your veterinarian will recommend a pericardiocentesis be performed to remove some of the fluid. This procedure involves your veterinarian inserting a needle through your dog’s side, into the sac around the heart. They can then remove the excess fluid. While for most dogs this procedure goes smoothly, around 10-15% will experience serious complications including a serious arrhythmia, bleeding into the chest, and other complications. This procedure may need to be repeated if fluid builds up around the heart again.

After the excess fluid has been removed, further treatment may be available. In some cases of hemangiosarcoma, the mass can be removed with a surgery. Chemotherapy is usually used after surgery as the tumor has almost always spread to other organs. In cases of chemodectoma, removal of the sac surrounding the heart can prolong survival. Chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be other options that can help prolong life or limit recurring clinical signs.

Long-term Care & Prognosis

Unfortunately, pericardial effusions are usually recurrent, although some dogs with inflammation as the cause will get better after just one episode of tapping the pericardial sac (pericardiocentesis).

Dogs with hemangiosarcoma of the right atrium often feel much better immediately after the fluid is removed. However, without additional treatment, the fluid often recurs within 1 day to 3 weeks. With surgical removal of a hemangiosarcoma mass and chemotherapy, dogs might live for 3-6 months. A variety of other options exist for hemangiosarcoma, although none of them result in a long-term cure.

With treatment for a chemodectoma, some dogs have lived for 6 months to 3 years after treatment.

If the cause of the pericardial effusion is not obvious based on the echo, the outcome may depend on whether the effusion reappears. Some owners elect for humane euthanasia when their pet begins to need frequent removal of the fluid from the pericardial sac. Sudden death can occur in dogs with pericardial disease. Evaluating your dog’s quality of life may help you and your veterinarian determine what is best in your dog’s case.

-

Overview

Heartworm disease is caused by a parasitic worm. Dogs are infected when they are bitten by an infected mosquito. The disease is more common in warmer climates, especially in the southern United States. However, dogs in almost all climates can be infected, especially during the hot summer months.

Large breed and outdoor dogs may be more prone to getting heartworm disease, although any dog can be infected with the parasite, and indoor dogs are no exception! Puppies can contract heartworm early in life, but a heartworm test will not become positive until 6-7 months after a mosquito bite.

Heartworm disease is easily preventable, and there are several preventative medication options. Your veterinarian can help explain the various options for prevention of heartworm disease. Prevention of heartworm disease is much safer, easier, and less expensive than treatment of heartworm disease. Speak with your veterinarian about the best heartworm preventative strategy for your dog.

For more information on heartworm disease and its treatment, visit the American Heartworm Society website.

-

Some cats and dogs are born with heart conditions due to parts of the heart not forming normally. These abnormalities can be the result of genetics or environmental factors.

The most common congenital heart diseases are patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), subaortic stenosis (SAS), pulmonic stenosis, and ventricular septal defect (VSD).

Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA)

Overview

A patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is a connection between the two largest blood vessels in the body, the aorta and the pulmonary artery. This connection is normally present before birth, but when it remains open (or patent) after birth it causes a problem. This abnormal connection, the PDA, places an extra workload on the heart. Over time this extra work of pumping too much blood can result in heart failure.

The great news is that a PDA can be fixed via surgery or with a catheter method. However, if one of these treatments is not pursued, approximately 40 to 70 percent of dogs with PDA will die by 1 year of age.

Symptoms

Female puppies are most prone to having a PDA. Some breeds are more predisposed to having a PDA including Bichon Frise, Poodle, Pomeranian, Keeshond, Maltese, Corgi, and Yorkshire Terriers, but any breed puppy can have a PDA. Puppies with a PDA may be stunted or smaller in size than their littermates. Kittens can also have PDA, but it is less common than in dogs.

Most puppies with a PDA show no symptoms. The first sign of a problem is usually a heart murmur detected on physical exam during a puppy vaccination visit.

If the PDA is severe, or if it is not corrected at an early age, animals may show difficulty breathing or develop a cough.

Diagnosis & Testing

During a physical exam, your veterinarian will likely detect a heart murmur in your puppy with a PDA. This murmur is due to the flow of blood across the PDA opening.

Listen to Normal dog heart sounds here.

Listen to a heart murmur from a dog with a PDA, or patent ductus arteriosus here.

Further workup for a heart murmur in a young animal may include an ECG or chest x-rays to see if the heart is enlarged. However, the best test to determine the source of the murmur in a young animal is an echocardiogram (echo). An echo lets your veterinarian see the size of the heart and identify the cause of the heart murmur. In animals with PDA, the abnormal connection and abnormal blood flow between the two blood vessels can be seen.

Treatment

A PDA is treated by a surgery to close the opening between the blood vessels. The surgery has a 90-98% success rate. There are several surgical options. The best option for your puppy or kitten will depend on their size and the specific appearance of their PDA.

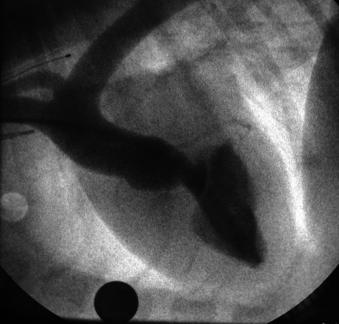

Closure of the PDA using a cardiac catheter is one of the common curative techniques. In most cases, the veterinary cardiologist will thread a catheter through a small incision in the back leg. This catheter is positioned over the PDA opening and a small device (coil or ACDO device) is released, and the device expands and closes the opening between the aorta and the pulmonary artery.

Surgical closure of the PDA via an open-chest surgery (thoracotomy) is also very successful when done by experienced veterinary surgeons. An incision is made over the chest, and the ribs are spread, to allow access to the heart. The PDA is then tied off with a loop of suture material.

Long-term Care & Prognosis

With catheter or surgical correction, your pet’s heart will usually return to normal size and he or she should live a normal lifespan. Dogs diagnosed with PDA should not be used for breeding.

Pulmonic Stenosis

Overview

Pulmonic stenosis, or pulmonary valve stenosis, is a common heart defect seen in puppies. In this condition, the valve between the right side of the heart (the right ventricle) and the main blood vessel to the lungs (the pulmonary artery) is abnormally narrow.

Because of the narrow vessel, the right side of the heart must work much harder to push blood into the lungs. This extra work causes the right side of the heart to thicken. Over time, the heart becomes less efficient and blood begins to back up.

Some dogs can live normal happy lives with mild pulmonic stenosis, while severe cases may develop congestive heart failure (usually fluid in the belly), fainting, or even sudden death.

Symptoms

The defect is present at birth but may not cause symptoms, and often is not detected until your veterinarian notices a heart murmur. Several breeds more commonly have pulmonic stenosis, these include the English Bulldog, Schnauzer, Beagle, Chihuahua, Terriers, Cocker Spaniel, Samoyed, and Basset Hound.

Most puppies with pulmonic stenosis will not show any symptoms. Even in dogs with severe pulmonic stenosis, symptoms like heart failure, fainting, or exercise limitation might not develop until middle age.

If the pulmonic stenosis is not caught early in life or worsens, symptoms may include fainting or swelling of the belly with fluid (congestive heart failure).

Diagnosis & Testing

Pulmonic stenosis is usually detected when the veterinarian hears a heart murmur during a routine visit.

X-rays may show an enlarged right side of the heart, and an ECG may show heart enlargement or irregular heart rhythms.

The best test to diagnose pulmonic stenosis is an echocardiogram (echo). An echo lets your veterinarian see the narrowed pulmonary valve. The echo will also reveal the degree of enlargement of the right side of the heart. An echo can be used to determine the severity of the condition and the pressure change from the right heart to the pulmonary artery. The higher the pressure change, the worse the pulmonic stenosis.

Animals with severe pulmonic stenosis are candidates for surgery or a catheter procedure to improve the situation.

Treatment

If your puppy is showing no symptoms and further testing detects only mild pulmonic stenosis, he or she may not require treatment. Routine veterinary visits and testing will help track your pet’s heart health throughout their life.

In dogs with severe pulmonic stenosis, a surgical or catheter procedure is usually recommended. Inflation of a balloon on the end of the catheter, to tear open the narrowed valve, is usually the treatment of choice (called balloon valvuloplasty). This is done by cardiac catheterization, where a catheter is passed into the heart via a blood vessel to determine the exact size and shape of the narrowing. Once the catheter with a deflated balloon is positioned over the narrowed valve, the balloon is quickly blown up to open up the valve. In most cases the balloon procedure is successful, and the pet’s heart health much improved.

Some dogs with pulmonic stenosis can develop heart failure. Because the narrowing of the artery causes the right side of the heart to enlarge, heart failure fluid usually accumulates in the belly. This fluid buildup indicates congestive heart failure. When congestive heart failure is present, medications may be prescribed including diuretics such as furosemide or spironolactone.

Long-term Care & Prognosis

Dogs diagnosed with pulmonic stenosis should not be used for breeding.

Mildly affected dogs may never show symptoms and live a normal, happy life.

Puppies with severe disease and those that show symptoms are at risk for major complications. Congestive heart failure can develop but often happens after 2-3 years of age. Fainting or sudden death is more likely to occur in dogs with severe disease. If surgery or a balloon dilation procedure is successful, dogs are much less likely to develop these severe complications of pulmonic stenosis.

Subaortic Stenosis (SAS) or Aortic Stenosis

Overview

Subaortic stenosis (also called SAS) is a common congenital condition in dogs. Dogs with SAS have a narrowing of the channel that connects the main pumping chamber of the left heart (the left ventricle) to the aorta. The aorta is the major artery that moves blood away from the heart to supply the rest of the body. In dogs, this narrowing is most often seen directly below the aortic valve (thus subaortic stenosis) but sometimes occurs in the aortic valve itself (aortic stenosis).

This narrowing means the left side of the heart must work much harder to pump blood into the aorta and the rest of the body. This extra work causes the left heart to thicken, and eventually this can cause irregular heartbeats (arrhythmias), sudden death or congestive heart failure.

View our Heart Disease Basics for more information on understanding heart function.

Symptoms & Signs

Aortic or subaortic stenosis are defects present at birth, although symptoms may never develop. Several dog breeds have a known predisposition for the condition, including Newfoundland, German Shepherd dog, Boxer, Golden Retriever, Bloodhound and German Shorthaired Pointer.

Most puppies with SAS show no symptoms and are only diagnosed after a heart murmur is detected.

Listen to Normal dog heart sounds here.

Listen to a heart murmur from a dog with subaortic stenosis (SAS) here.

If severely affected, dogs may have fainting episodes. Unfortunately, the most common symptom seen in SAS is sudden death.

If a dog with SAS develops congestive heart failure, symptoms may include difficulty breathing, coughing, decreased ability to exercise, and other signs of heart failure.

Diagnosis & Testing

A heart murmur discovered during a routine physical exam is the most common initial finding for a dog with SAS.

While chest x-rays and an ECG can be helpful in evaluating dogs with SAS, the best test to prove the cause of the murmur and evaluate the disease severity is an echocardiogram (echo). In dogs with SAS, an echo will show a thickened left ventricular muscle. The narrowing of the channel between the left heart and aorta will be seen. Using Doppler on echo, the veterinary cardiologist can measure the pressure change between the left heart and aorta. The higher the pressure change the more serious the SAS.

Treatment

Treatment of SAS is difficult. None of the currently available treatment options has been shown to result in consistent, marked improvement. Many veterinary cardiologists use beta-blocker drugs, like atenolol, to try to reduce the chance for sudden death or slow the thickening of the heart walls.

Surgical options have been described, including catheter options that involve expanding a balloon in the region of the narrowing (balloon dilation). Some veterinary cardiologists use balloons with thin razor blades on the balloon, and these are called cutting balloons. The severity of the condition can be improved with the balloon in most dogs, however, many dogs have the return of severe disease later in life.

If a dog with SAS develops congestive heart failure, medications will be prescribed to control the heart failure. Dogs with irregular heartbeats (called cardiac arrhythmias) are at higher risk for collapse or sudden death and these dogs are usually treated with antiarrhythmic drugs (e.g., Sotalol, Mexiletine, Amiodarone).

Long-term Care & Prognosis

Dogs with SAS should not be bred as the defect could be passed to their puppies. Even related dogs that are unaffected might carry the genes for the disease, so caution is advised for breeding dogs related to those with SAS.

Dogs with mild SAS and no symptoms usually live a normal lifespan with no treatment.

Severely affected dogs are prone to developing congestive heart failure and can die suddenly. Many dogs with moderate to severe SAS can live for 4-6 years, but those with the most severe disease might die by 1-3 years of age. Dogs with SAS are at increased risk for getting an infection in their heart, so antibiotics are typically recommended if they have surgery or get a wound.

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

Overview

A ventricular septal defect, or VSD, is a congenital heart condition present at birth. The condition involves an abnormal connection between the two ventricles of the heart. The ventricles of the heart are the main pumping chambers of the heart. Because the pressure is higher on the left side of the heart, blood flows from the left ventricle through the hole in the septum (the muscular wall separating the heart chambers) and into the right ventricle.

Because the heart must pump extra blood with each heartbeat to account for the leak, the heart is larger than normal, and there can be extra blood flow through the lungs. The consequences of the defect depend greatly upon the size of the hole between the right and left ventricles. Dogs with a large VSD can develop congestive heart failure.

Symptoms & Signs

Most dogs with VSDs show no symptoms. The defect is most often diagnosed after a heart murmur is detected on a routine physical exam. The English Bulldog and Keeshond are more prone to VSD.

If the VSD is severe, congestive heart failure can develop, with symptoms including difficulty breathing, coughing, decreased ability to exercise, and other signs of heart failure. See our Symptoms of Heart Disease tab for more details.

Diagnosis & Testing

Most dogs with a VSD have a loud heart murmur detected during a routine physical exam. This, like any loud murmur in a young animal, requires further testing.

An echocardiogram (echo) is the best test to identify the cause of the heart murmur. The echo will let your veterinarian see the connection between the left and right heart -- the hole that is present in the muscle between these two chambers. The echo can also help determine the severity of the VSD.

Chest x-rays are often part of a cardiac workup. Depending on the size and severity of the VSD, x-rays may be completely normal, or they may show an enlarged heart with fluid in the lungs.

Treatment

Dogs with a small VSD will usually not require treatment. Regular veterinary visits will ensure any worsening of the defect is detected early. Your veterinarian may recommend periodic echocardiograms or x-rays to track heart size. Owners should learn to measure breathing rate and effort in order to monitor their dog carefully for symptoms of heart failure.

Dogs with moderate to large-sized VSD can develop congestive heart failure. If heart failure develops, dogs may be prescribed drugs like furosemide, pimobendan, and an ACE inhibitor.

A low-sodium diet and other nutritional changes may be recommended. Exercise restriction is also usually recommended.

Surgical correction of a VSD is possible and may be helpful in some cases. Surgery is likely most successful when done before the development of heart failure. Your veterinary cardiologist can advise you about the options.

Long-term Care & Prognosis

Dogs with a VSD should not be bred as the defect could be passed to their puppies.

The prognosis for a dog with a VSD depends greatly on the size of the hole. Dogs with small VSDs may never show symptoms and live a normal lifespan.

Dogs with large VSDs may develop congestive heart failure. With treatment, recheck visits, and careful adjustment of medications, dogs with congestive heart failure can live for 6-18 months.