Heart Disease - Cats

Heart Disease Resources: Basics | Symptoms | Diagnosis | Dogs | Cats | Treatments | Medications | Nutrition | Forms

Because cats can hide their heart disease well, detecting your cat’s heart condition can be very difficult. Cats usually will not show outward symptoms of heart disease until the disease is advanced. Also, cats with heart disease are less likely to have a heart murmur heard with a stethoscope and this can further delay diagnosis.

Some of the most common heart conditions in cats are:

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) – the walls of the heart are too thick

- Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) - the walls are thin and the heart contracts weakly

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) – the heart does not fill well with blood

- Congenital heart disease like Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) - born with a hole in the heart

- Arterial thromboembolism (ATE) – clot lodges in a blood vessel and blocks blood flow

- Systemic hypertension – high blood pressure

- Hyperthyroidism – excess thyroid hormone results in a fast and overstimulated heart

Cats can also get heartworm disease. Diagnosing cats with heartworm disease in cats is difficult and there are currently limited treatment options. A monthly heartworm preventative is the best option for protecting your cat. For more information on heartworm disease, please visit the American Heartworm Society's website.

The information included in this section covers the most commonly diagnosed feline heart diseases and their complications. However, because every cat is unique, your cat may not show the typical symptoms so diagnosis and treatment will be specific for your cat. Your veterinarian can answer specific questions you have about your cat’s condition. Visit our other pages for more information on basic heart function, symptoms of heart disease, diagnosing heart disease, nutrition for heart disease, and helpful forms and resources.

-

Overview

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (also called HCM) is the most common heart disease in cats. In this disease, the heart walls become drastically thickened. The thickened heart is stiff, and the efficient function of the heart is compromised. Blood backs up into the lungs and causes difficulty breathing (congestive heart failure). Blood clots can form in the heart and migrate to other parts of the body (called arterial thromboembolism or ATE) resulting in a sudden inability to use one or more of the legs.

Symptoms

Most cats with HCM are young to middle-aged (around 6-12 years old) but the disease can affect cats of any age. Maine Coon cats and Ragdoll cats are genetically predisposed to HCM. Genetic testing can be done in Maine Coon cats and Ragdolls, including testing done at the North Carolina State University Veterinary Genetics Laboratory.

Many cats with HCM show no symptoms. You may only learn of your cat’s heart condition if your veterinarian detects a heart murmur or irregular heart rhythm during a routine visit, but many cats with HCM do not have a heart murmur. Treatment may be recommended, even in a cat without symptoms, in an attempt to delay the onset of heart failure or a blood clot.

The first visible symptom of HCM is often sudden difficulty breathing or a sudden lameness, which sometimes happens following a stressful event. This event could be something veterinary-related (like a surgery or a steroid medication) or it could be due to lifestyle changes (like a new pet or a change in the living situation). Prior to this event, you may not have known your cat had a heart condition. However, your cat has likely been living with a heart condition for some time, maybe many years.

Cats with HCM and heart failure may exhibit rapid breathing (faster than 35 breaths per minute at rest), or labored breathing, or in some cases open mouth breathing. Many cats with difficulty breathing will have a reduced appetite or they might hide in a quiet place, like under the bed or in a closet. In some cats, the difficulty breathing is not apparent until they are on their way to the veterinarian for hiding, loss of appetite, or just seeming sick. If you notice your cat is breathing heavily, this is often an emergency and you should contact your veterinarian.

Fainting can occur in cats with HCM. Your cat may fall over unexpectedly and lose consciousness. If your cat appears to have fainted or had a seizure, contact your veterinarian right away.

Cats with HCM are prone to developing dangerous blood clots, called arterial thromboembolism (ATE). These blood clots get stuck in the blood vessels supplying your cat’s limbs, often the back legs, and cause sudden paralysis. If you notice your cat appears paralyzed or is unable to put weight on one or more of their legs, contact your veterinarian right away. These blood clots can be life-threatening and are a veterinary emergency.

Other symptoms of HCM in cats can be much more subtle. Your cat may simply become less social and try to hide more. Some cats no longer want to play, or act more tired, or start to open mouth breathe after exercise. Or your cat may start urinating outside the litterbox, refuse food, or eat less than normal.

Diagnosis & Testing

The diagnosis of a cat with possible HCM begins with a complete physical examination. Your veterinarian will listen for a heart murmur or irregular heart rhythm. They will also listen to your cat’s lungs. If your cat has had trouble breathing, your veterinarian may hear abnormal lung sounds (called crackles) that occur with the fluid buildup seen with congestive heart failure.

If your cat has an irregular heart rhythm, also called an arrhythmia, an ECG helps determine the type of irregular heartbeat.

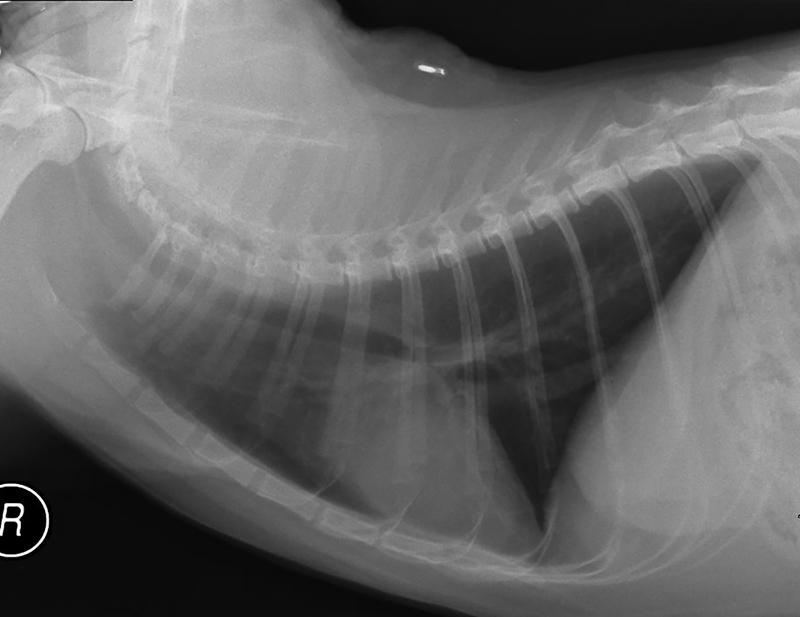

Chest x-rays are often taken for cats with HCM. Your veterinarian will measure the size of your cat’s heart, as cats with HCM often have enlarged hearts. X-rays can also reveal issues in the lungs. Fluid buildup in the lungs can indicate congestive heart failure and the x-rays can help differentiate between heart failure and other lung diseases such as pneumonia or asthma.

The best test for diagnosing HCM in cats is an echocardiogram (echo). An echo shows your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist whether your cat’s heart has the thickened walls characteristic of HCM. The echo can also indicate if your cat is at higher risk for developing a dangerous blood clot.

Your veterinarian may request bloodwork. Routine bloodwork ensures your cat’s other organs are healthy enough for medication and helps your veterinarian select the best medications for your cat. Specific blood tests may be required, but a test called BNP (or NT-proBNP) can be very helpful to determine whether additional testing for heart disease is likely to be helpful.

A thyroid test (called a T4) is often indicated for middle-aged to older cats. The level of T4 in the blood reflects the health of your cat’s thyroid. Heart disease can be worsened by excess thyroid function (called hyperthyroidism). Management of thyroid disease can make controlling heart disease easier.

Treatment

The treatment of your cat’s HCM depends on the severity of the disease. Cats with very mild disease may not require treatment. However, if your cat has advanced HCM, 3 to 5 medications may be needed to control heart disease. The types and doses of medications are best selected after an echo and bloodwork have been performed.

Drugs that are commonly recommended for cats with HCM include furosemide (Lasix), an ACE inhibitor, beta-blocking drugs like atenolol or carvedilol, pimobendan, and clopidogrel.

A low-sodium diet may also be recommended, depending on the severity of heart disease. Other nutritional changes may also be recommended. See the Nutrition page for more information about nutritional recommendations for cats with heart disease.

Long-term Care & Outcomes

Many cats with HCM can be well-managed with medications. However, cats can get life-threatening heart failure or blood clots, and these are sometimes very difficult to treat.

It is ideal to find heart disease before your cat has a crisis. Changes to the diet can be made and medications started to delay the time until heart failure or a clot develops.

In general, the outcome for cats with HCM depends on whether they are showing symptoms or not. Cats without any symptoms often live with heart disease for a long time, whereas cats with a clot to both back legs (arterial thromboembolism) might not survive the first clot episode.

Cats without any symptoms of HCM can live for many years before a problem arises. Periodic rechecks with echo can help determine if the disease is progressing and whether drugs should be added or adjusted.

You should watch your cat for trouble breathing, weakness, tiredness, or decreased appetite. It is also very important to watch for signs of a blood clot such as sudden onset pain, weakness, or paralysis in your cat’s back legs.

Another possible outcome of HCM is abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmia), which can sometimes cause sudden death.

Cats with heart failure and HCM usually need at least 3-4 medications to control symptoms and prevent clot formation. The doses of medications are sometimes adjusted based on breathing rate and effort (monitoring form). The dose of furosemide (Lasix) may be increased to control fast or labored breathing (see videos of normal and abnormal breathing).

Bloodwork might need to be repeated every few months to ensure good control of the heart disease without a negative impact on the kidneys or electrolyte levels. Your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist may request regular follow-up visits to adjust medications or recheck the echo after starting treatment.

Many cats with HCM and heart failure can live for 6 months or longer with frequent recheck exams and adjustment of medications, and some cats can live 1-3 years or longer after the onset of heart failure.

Blood clots are a common complication of HCM, developing in 10-20% of cats. This complication can be very difficult to treat and not all cats with regain normal leg function and be able to walk again. For those cats that do regain leg function, this can take many weeks. For cats that are not euthanized in the first 24 hours, the average time until another clot or episode of heart failure is usually 2 to 6 months, although some cats are lucky and survive for many years. As the disease progresses, some owners may determine their cat’s quality of life has diminished and elect to put their cat to sleep.

Your cat’s individual prognosis depends upon many factors and your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist will discuss what you can expect for your cat.

-

Overview

In DCM, the heart chambers become bigger, while the heart walls thin and contract weakly. As a result, the heart cannot push blood forward to the rest of the body. Congestive heart failure commonly develops in cats with DCM.

Cats can develop DCM as a result of a taurine deficiency. As cats require taurine in their diet (as opposed to most other species), cats fed a diet that is low in taurine can develop heart disease. There are minimum required levels of taurine in all cat foods but unbalanced homemade, vegetarian or vegan or raw diets may not have enough. Even some commercial cat foods that are not intended to be nutritionally complete and balanced (i.e. for intermittent or supplemental use) can be deficient in taurine. Cats on these diets are more likely to develop taurine-deficient DCM.

Symptoms

The average age of cats with DCM is about 9 years but cats of any breed or age can develop DCM. Several cat breeds may be more prone to developing to DCM, including Burmese, Siamese, and Abyssinian.

Cats with DCM have symptoms that are very similar to cats with HCM. Cats often hide their diseases until they are in advanced stages, so cats with DCM may show no symptoms until heart disease is very advanced. Cats with DCM may be first identified when they develop difficulty breathing or blood clots.

Diagnosis & Testing

Testing for cats with DCM is very similar to cats with HCM. One difference is that a taurine test may be recommended to determine whether your cat’s DCM is due to a taurine deficiency or requires taurine supplementation.

Tests that are often done for cats with DCM include an ECG, chest x-rays, blood tests, and an echocardiogram. Besides the blood taurine level, other blood tests that might be done include tests of kidney function, electrolytes, thyroid test, or which is a blood marker of the heart enlargement.

An echocardiogram (echo) will allow your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist to see the dilation of the heart chambers and the thin walls and decreased strength of the heart’s contraction characteristic of DCM.

Treatment

Treatment for a cat with DCM is usually required when the cat has congestive heart failure. Medications used to treat congestive heart failure in cats are furosemide, pimobendan, an ACE inhibitor, and often anticlotting drug-like clopidogrel.

If your cat’s DCM is due to a taurine deficiency, a taurine supplement is recommended. Taurine supplementation is typically recommended until the blood taurine results are back.

Recently, the FDA has been investigating diet-associated DCM in dogs. While this mostly seems to occur in dogs, cats might also be affected so we recommend changing your cat’s diet if he or she has been eating a suspected diet. For more information on diet-associated DCM, please click this link.

A low-sodium diet may also be recommended, depending on the severity of heart disease. Other nutritional changes may also be recommended. See the Nutrition for more information about nutritional recommendations for cats with heart disease.

Long-term Care & Prognosis

Cats with DCM that are in congestive heart failure will require recheck exams and follow up bloodwork every few months or even more frequently. This ensures the medications are working effectively and the kidneys are not failing. Your veterinary cardiologist will also recommend following your cat’s echo.

Cats with DCM should ideally remain indoors only. Cats generally limit their own activity, but strenuous activity such as chasing laser pointers should be avoided.

Optimal nutrition is crucial for your cat’s long-term care and quality of life. See our Nutrition section for tips on optimizing your cat’s diet.

Cats with taurine-deficient or diet-associated DCM should have a follow-up echo 2-3 months after treatment was started. Cats with taurine-responsive DCM typically have a favorable prognosis, often having a normal lifespan.

If your cat’s DCM is not caused by a taurine deficiency, the prognosis is much less favorable. With medications and treatment, cats with DCM and congestive heart failure might only live several weeks to months after diagnosis.

Life-threatening blood clots (arterial thromboembolism, ATE) are a common complication of all heart disease in cats, including DCM.

Other cats may experience a severe arrhythmia that causes sudden death. As the disease progresses, some owners may determine their cat’s quality of life has diminished and elect to put their cat to sleep.

Your cat’s individual prognosis depends upon many factors and your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist will discuss what you can expect for your cat.

-

Overview

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is a condition in cats where scar tissue forms in the heart muscle. This scar tissue makes it harder for the heart to fill and pump blood.

Cats with RCM are prone to developing life-threatening blood clots called arterial thromboembolisms (ATE). Cats with RCM are also likely to progress to congestive heart failure.

Symptoms

Most cats with RCM are diagnosed at middle to older age. Any breed of cat can develop RCM.

Symptoms are very similar to those seen with HCM. Cats with RCM often develop congestive heart failure or arterial thromboembolism.

Diagnosis & Testing

Diagnostic testing for RCM is very similar to what is outlined for HCM above. In addition to listening for a heart murmur or abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia), tests that are often done include an ECG, chest x-rays, blood tests and an echocardiogram. Echocardiographic findings of RCM can include scar tissue formation in the heart muscle or abnormal blood flow within the heart.

Treatment

Cats with RCM and heart failure are treated with the same medications as most other cats with heart muscle disorders (see HCM treatment above). Commonly prescribed medications include furosemide, pimobendan, an ACE inhibitor, and clopidogrel. Check out our tips for administering pills.

Cats with severe heart failure will often need to be hospitalized to start or adjust their medications.

Long-term Care & Prognosis

Cats with RCM in heart failure will require frequent veterinary visits to evaluate the overall health and effectiveness of medications. Owners should routinely record their cat’s breathing rate. This can help determine whether medications are properly dosed. Use our monitoring breathing rate forms.

Maintaining your cat’s appetite and body composition is a crucial component of care for a cat with heart failure. See our tips for stimulating a picky eater.

Managing cats with RCM can be challenging. Many cats are already in heart failure when diagnosed and complications are common. Blood blots, worsening heart failure, medication side effects, and sudden death are possible complications. As the disease progresses, some owners may determine their cat’s quality of life has diminished and elect to put their cat to sleep.

Your cat’s individual prognosis depends upon many factors and your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist will discuss what you can expect for your cat with RCM.

-

Overview

Congenital heart diseases are defects in the heart that are present at birth. Congenital heart diseases are less common in cats than dogs. The most common heart defect in cats is a ventricular septal defect (VSD). Cats get other congenital defects, and some of these defects are outlined in the Dog Congenital Heart Disease section.

Some cats with congenital heart defects may never show symptoms and live a completely normal life. Cats that begin to show symptoms as a result of their heart defect will require treatment. Treatment for congenital heart defects can include medications or surgery.

Your veterinarian or veterinary cardiologist will determine the best treatment and management options for your cat with congenital heart disease.

-

Overview

Arterial or aortic thromboembolism (ATE) is a common and serious complication of heart disease in cats. It is most often seen in cats with heart muscle diseases such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), or restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM).

In cats with heart disease that have dilated heart chambers, blood flow slows down and becomes more prone to forming an unwanted clot. Blood clots usually form in the left atrium of the heart. This clot often dislodges and is carried with the flow of blood until it gets stuck in an artery, often at the end of the aorta, the largest artery of the body. Wherever the clot stops, the blood flow past this region is drastically reduced. If this happens at the end of the aorta, it is often called a “saddle thrombus”. In this site, the lodged clot stops blood flow to the hind legs. Without blood flow, the limbs become weak or paralyzed, and eventually, the muscle cells start to die from lack of blood flow.

Clots can become stuck in other areas of the body such as the front legs, kidney, digestive tract, or the brain, although these locations are less common.

An ATE is an emergency, and your cat should see a veterinarian right away.

Symptoms

Cats with heart disease are prone to developing an ATE. Approximately 10-20% of cats with significant heart disease develop an ATE. Unfortunately, an acute ATE is often the very first indication that a cat has heart disease, before any other symptoms are present.

The most common sign of an ATE is a sudden weakness or paralysis of your cat’s hind legs. However, an ATE may affect a single leg or other parts of the body. The legs will often feel cool or cold to the touch. Paw pads or the nail beds may look blue or purple.

An ATE is usually quite painful and can be disorienting, so your cat will likely meow loudly or make other noises. Exercise caution, as your cat may act out aggressively in response to the pain or disorientation.

Cats with an ATE may breathe rapidly or breath with an open mouth. This may be due to heart failure or may be related to discomfort. This is an emergency, and your cat should see a veterinarian right away.

Diagnosis & Testing

The visible symptoms of an ATE are often enough for diagnosis and initiation of immediate emergency treatment. In addition to the symptoms noted above, your cat’s pulses in the back legs may be difficult for your veterinarian to feel due to the reduced blood flow.

Most cats with ATE have heart disease, but there are a few other causes. Your veterinarian may want to do a chest x-ray in order to look for congestive heart failure and or to search for a lung mass since this is one of the less common causes of ATE. Since most cats with ATE have heart disease, an echocardiogram (echo) is usually indicated. On the echo, some cats with heart disease may have a clot in the left atrium of the heart, or other changes in the heart.

Treatment

An ATE is a veterinary emergency. Treatment will involve hospitalization.

Some veterinarians worry that cats will never regain function of the limbs, and since cats are often painful, they might discuss the option of euthanasia. Some cats will regain function, and most cats with a clot to the front leg will walk again, so in our view it is quite reasonable to pursue treatment, at least for 24-48 hours to see how much function starts to come back.

During hospitalization your cat will be treated with anticoagulant to prevent additional clot formation and to help the body break down the existing clot. Pain medication will also be administered. If your cat has congestive heart failure, medication to control the fluid build-up will also be started.

Long-term Care & Prognosis

After release from the hospital, cats with an ATE typically require anti-clotting medications, like clopidogrel, and often significant additional care. Physical therapy is often used to help your cat regain full function of his legs. Cats that have not yet regained enough function to their rear limbs may have difficulty standing to urinate and might need your help during urination. Your veterinarian can show you how to do this.

Unfortunately, many cats who experience an ATE are prone to more clots, or to heart failure, even with anti-clotting medication and drugs for the heart. For cats that survive the first 24 hours, the typical survival time is 2 to 12 months, but some cats have been known to live for many years.

-

Overview

Systemic hypertension is high blood pressure in the arteries throughout the body. Unlike in people, cats (and dogs) with systemic hypertension usually have an underlying disease that has caused the elevated blood pressure. A variety of diseases can cause systemic hypertension in cats, including kidney disease and changes in certain hormones. Blood pressure can usually be measured by noninvasive methods that include placing a cuff around a leg or the tail.

If your cat is diagnosed with hypertension, your veterinarian might recommend other tests to check on the kidneys, the thyroid gland, or the adrenal gland.

Cats with systemic hypertension often develop heart disease. This is usually some thickening of the muscular walls of the heart’s main pumping chamber, the left ventricle. Other organs that might suffer due to high blood pressure include the eyes, the brain, and the kidneys.

Treatment for systemic hypertension includes medications and management of the underlying condition that caused the high blood pressure.

-

Overview

Hyperthyroidism is a common condition in older cats. In this condition, the thyroid gland overproduces thyroid hormones. This usually happens due to an enlarged thyroid gland, which is found in the neck. Hormone overproduction puts the body in overdrive, causing the overall metabolism to increase. The heart must work harder to keep up with the increased demands from the rest of the body. The heart can beat too fast, or irregular heartbeats can develop (called arrhythmias), or the heart can start to enlarge in response to the increased workload.

Cats with hyperthyroidism usually appear thin with weight loss despite an excellent appetite. Hyperthyroid cats are sometimes nervous, excitable, irritable, or even weak and lethargic. If a heart issue or heart failure develops, cats might have difficulty breathing or even become uninterested in food.

A blood test measuring the level of thyroid hormone (T4) in your cat’s body will help your veterinarian diagnose hyperthyroidism. Further testing, like an ECG, blood pressure, chest x-ray, or an echo, may be needed to determine if heart disease is also present.

Treatment for hyperthyroidism can involve medications that will decrease the thyroid hormone levels, a special diet, radiation therapy, or surgery. If heart failure is present, medications will be needed to support the heart. One good piece of news is that successful treatment of hyperthyroidism can result in significant improvement in the heart changes in many cats. Your veterinarian will determine the best treatment options for your cat’s condition.