Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

The bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) allows us to see deep within the horse’s lungs to determine if there is inflammation and if so, what the inflammation looks like. The BAL is sometimes called a lung wash because we literally wash the smallest airways and alveoli (tiny lung sacs where oxygen is exchanged) with sterile saline. When we suction back that fluid, we bring cells and mucus out of the lung, and then we make a cytology of that fluid (a slide that we can look at under the microscope). The BAL can be done blindly in the field with a specialized silicone tube, called a Bivona BAL tube. This is a very useful technique and is practical for ambulatory veterinarians. At Cummings, we prefer to do a full bronchoscopy. This allows us to examine all the airways as we obtain the BAL, and it also allows us to examine the upper airway to determine if there are any abnormalities that may be contributing to a horse’s cough or nasal discharge in addition to IAD.

Clients and referring veterinarians sometimes ask us why we don’t just do a tracheal aspirate using a regular endoscope, which is a very simple procedure and doesn’t require any specialized equipment. The answer is that this method takes cells from what we term the ‘tracheal puddle’ toward the end of the trachea, and multiple studies have shown that what we see in the tracheal puddle does not reflect what we see in the BAL. Quite simply, the two methods are not equivalent, and the tracheal aspirate is inferior to the BAL if we want to know what is going on in the small airways, which is what we care about with IAD horses.

BAL Technique

The bronchoalveolar lavage is best used in cases where we suspect that the disease we are looking for is diffuse, and when we are not planning to culture the fluid. It is most commonly used for suspected IAD or heaves, but can also be useful for interstitial pneumonia, fungal pneumonia or silicosis, for example.

Your veterinarian will listen to your horse’s heart with a stethoscope before performing the BAL. Although the BAL is common and safe, we prefer not to perform it on a horse with cardiac arrhythmia or a very high respiratory rate. Your veterinarian will also warn you that your horse is likely to cough a lot during the procedure and while it may sound alarming, it should be expected. Before performing the BAL, your veterinarian will heavily sedate your horse. There are several reasons why heavy sedation is essential: firstly, we are aware that when people experience a BAL, they don't feel pain, but they do report feeling panicky. We want to sedate the horse to keep it from feeling any unpleasant sensations; secondly, we need the tube to go into the horse’s trachea and not the esophagus, so we have to stretch the head out and encourage the horse to leave the airway open; and finally, we want to be able to wedge the tube or endoscope firmly in the lower airway so that we get a true picture of the cells in that area. It will look to you as though your veterinarian is using a lot of sterile fluid to wash the lungs – and it is a lot. We use half a liter of sterile fluid to do a BAL. However, your horse’s lungs are enormous and any fluid that is not suctioned back is rapidly absorbed by the great veins in the lungs, so there is no risk of drowning your horse, as clients sometimes fear. By using a large, standard amount of fluid, we make sure that we get repeatable results that can be compared to known standards – this is critical for a correct diagnosis. Once your veterinarian has instilled and suctioned back the full 500mls of fluid, they will place it on ice to keep the cells happy until they are back at the clinic where slides can be made or the fluid can be sent to our laboratory for analysis.

BAL Cytology

Request a BAL Consult

When you have your sample read at the Tufts Bronchoalveolar Lavage Cytology Service, not only do you get a cytological diagnosis, but you also have access to clinical advice.

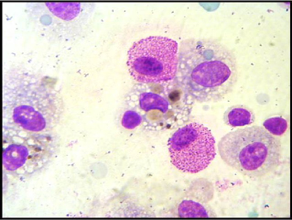

Horses normally have a scant amount of mucus in their lower airways, along with alveolar macrophages, lymphocytes and a scant number of neutrophils, mast cells and eosinophil.

Alveolar macrophages are the predominant cells in the airways of most mammals, including humans, but they only account for approximately 60% of the total cell population in horses; lymphocytes are the other heavy hitters, accounting for about 40% of the total cell population in the lungs. Normal horses have less than 5% neutrophils, less than 2% mast cells and less than 0.5 % eosinophils. Let’s talk for a minute about what these cells do.We think of alveolar macrophages as the normal cells of the lung. Alveolar macrophages are the ‘clean-up’ cells that are part of the innate immune system. They recognize particulates that don’t belong in the lung and get rid of those particulates, including bacteria, before they can cause damage.

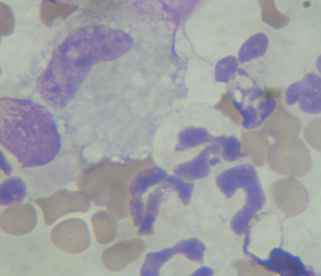

In the picture here you can see one of the worst offenders in equine lungs – a spore from one of the many fungi that are found in even the best hay. This is not an infection, but more like a foreign body to which the horse’s lungs are mounting an inflammatory response. Lymphocytes are rare in the lower lungs of most species other than horses. They are important to immune function but have an important role in the adaptive immune system, which the body uses to recognize specific pathogens and have what is termed ‘memory’. Neutrophils are scarce in the healthy lung of any species, but proliferate in horses with heaves/RAO and also more severe or chronic IAD.

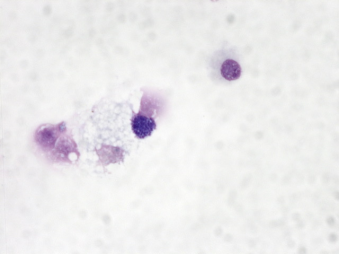

Mast cells are important in allergic diseases, and although their staining characteristics are very aesthetically pleasing, the beautifully staining purple granules are the very things that cause many of the symptoms associated with respiratory allergies, including bronchospasm and cough. Eosinophils are rare in the healthy horse but can be seen more frequently in the BALF in the summertime, or in horses that have intestinal parasites. Less commonly, we see goblet cells, which produce mucus and both ciliated and non-ciliated epithelial cells. Epithelial cells should be rare to absent in the normal BALF: we see them more frequently in horses with cough or who have had viral respiratory disease in the recent past.

Although some laboratories suggest straining BALF to remove mucus, our laboratory prefers not to, as microscopic analysis of the mucus itself can be important to the diagnosis of disease, and mucus often has trapped particulates such as pollen and mold spores, allowing the cytologist to detect the original problem.

Ready to Find Out More?

Download Dr. Mazan's Equine Respiratory Health e-book for a detailed understanding of equine respiratory health.