Equine Asthma

Many of you have probably heard of the severe respiratory disease known as heaves, otherwise known as recurrent airway obstruction (RAO) and inflammatory airway disease (IAD). There are also other names to describe airway conditions including allergic airway disease, small airway disease and COPD.

All of these diseases fall under the spectrum of equine asthma, and horses with any form of equine asthma have airway inflammation that causes the signs you recognize, ranging from poor performance to a cough, nasal discharge or overt respiratory distress.

We’ve known for a very long time that the horse’s environment is responsible for most of the ills that beset our equine companions. Aristotle noted that horses ‘at pasture [were] largely free from disease’; while Louise Hill Curth described a condition known as ‘heartache’, which was probably heaves in ‘A plaine and easie waie to remedie a horse': Equine Medicine in Early Modern England.

Equine asthma, whether IAD or heaves, is usually treatable, but not necessarily curable. It can take a lifetime of management, but with an accurate diagnosis, proper treatment and environmental improvements, most horses can return to athletic function.

Signs

It’s easy to recognize when a horse has a flare-up of heaves. It is the horse that everyone in the barn knows, the one who gets a bad batch of hay and then stands in the stall with nostrils flaring and sides heaving, desperately trying to get air. It can be a little harder to recognize a horse with IAD, especially because these two diseases are on a continuum of severity, and horses with mild heaves can sometimes look pretty normal. So, what does a horse with IAD look like? It depends on what the horse does for a living.

Racehorses, whether they are Thoroughbreds, Quarter Horses or barrel racers, need every bit of oxygen they can get. Even the smallest amount of respiratory disease can show up as decreased performance without any other distinguishing signs such as a cough, nasal discharge or visibly abnormal breathing effort. The classic description of a racehorse with IAD is that he ‘quit at the ¾ mark.’ The Kentucky Derby horse that loses by a length (which seems like a huge amount in a race) is only about 0.15 seconds slower than the horse ahead of him, and he may well have lost because he had IAD.

IAD shows up in young racehorses and can be very difficult to diagnose without advanced techniques. High-goal polo ponies also live on the oxygen edge. During a seven-minute chukka, polo ponies can cover three miles at a gallop going up to 30 miles per hour. As with racehorses, you may never hear them cough, and it’s unlikely that they’ll have nasal discharge, but they might get ridden off as you gallop with an opponent towards the ball. High-level event horses, competitive endurance horses and jumpers may also have poor performance without showing other identifiable signs of respiratory impairment. Occasionally, however, the rider or trainer may note that it takes longer for the horse’s respiratory rate to return to normal after peak exercise, or that the horse ‘blows’ more than other horses after exercise.

Horses have been blessed with an extraordinarily large respiratory reserve. Have you ever wondered why we race horses and not cattle, who after all, are about the same size as horses? It is most likely because horses have lungs that are almost twice the size of cattle lungs. This means that unless horses are at their peak performance, they probably don’t need all the oxygen that their lungs can deliver. Consequently, we tend not to notice the beginning stages of IAD.

IAD can even go undetected in a high-level dressage horse, a hunter/jumper or reining horse for a long time. It isn’t until these athletes start to cough or have a noticeable nasal discharge that we look for evidence of respiratory disease. Many riders will describe how their horse practically pulls them out of the saddle with a cough at the beginning of a ride. Unfortunately, because IAD is so common, many people think it is normal for a horse to cough at the beginning of a ride. Coughing is common but not necessarily normal. Coughing is a sign that all is not well with the respiratory system, and the most common cause in horses is IAD. An astute rider or trainer may notice earlier signs, which can include: trouble getting a horse on the bit or even noticing that a horse is making a respiratory noise when he’s on the bit; taking down a rail; swapping leads; or just a generalized ‘lack of brilliance’.

All of these non-specific signs can be a warning that something is wrong with the horse’s respiratory system.

Although heaves are classically a disease of stabled horses, we find that many IAD horses in the New England area have exacerbations of the disease in the late spring and summer. They tend to have the most severe signs when it is hot and moist. Many horses also show worse signs with the advent of pollen season, especially when evergreens surround their pastures. Symptoms are also often worse when indoor arenas become dusty or barn management practices cause more dust in the air.

Causes

Both IAD and heaves are diseases caused by poor air quality and unfortunately, agricultural environments and farms are replete with organic dust and other particulates that can cause profound irritation to the airways of horses, humans and other creatures sharing the environment. This irritation results in inflammation in even non-allergic individuals. Many cases of IAD show no evidence of actual allergic disease, whereas the more severe disease, heaves, has a clear allergic component. Although horses with mild-to-moderate heaves can appear normal in a physical examination when they are kept in a dust-free environment, clinical heaves, with obvious breathing effort, cough and nasal discharge, can easily be induced in these individuals by exposing them to moldy hay.

Horses with IAD, on the other hand, often have no signs of allergies at all. Instead, IAD in these horses is similar to what is called occupational asthma in people. Although we commonly think of asthma as an allergic disease in people, in reality, many agricultural workers or those who live or work in dusty environments – such as livestock farms, cotton factories, woodworking shops or landscaping – can develop asthma without any underlying allergic disorder. For these workers, the particulates, endotoxin and beta glucan levels are so high that the airways naturally produce a profound inflammatory response. Unfortunately for horses, their occupations often include living in environments that are neither good for horse lungs nor human lungs.

Even the best barns are laden with endotoxins (bits and pieces of dead, gram-negative bacteria that still triggers profound inflammation in the lungs), beta-glucans from molds, mites and other insects, and ammonia gas from urine. Viable bacteria can be found in the breathable air in many indoor arenas. If you were to feed your horse the best quality hay that money could buy, it would still be full of mold spores that do not cause infection but that are small enough to be inhaled into the tiniest airways in the lungs where they trigger airway inflammation. Tractors in some barns, rely on diesel engines to pull manure or hay wagons. This fuel is particularly problematic because the particulates that it contains cause oxidative damage to the lungs. Air pollution does the same thing and unfortunately, because of the way the winds blow, even seemingly pristine areas of New England can be affected by pollution that originates, for example, in the Midwest.

If you have ever wondered what this is doing to your own lungs, you would be wise to be a little worried. We encourage all of our clients to clean up their barns to keep their horses and themselves healthy. A study from our laboratory (Mazan 2009) showed that people who spend 10 or more hours in a horse barn have a markedly increased risk (up to 10 times) of developing respiratory symptoms compatible with asthma. The high particulate, endotoxin, beta-glucan and ammonia level that hurts horses' lungs also triggers inflammation in our lungs.

Recent work from our laboratory (Houtsma 2015), as well as evidence from other researchers, suggests that a disease, similar to the situation in children, can trigger or worsen disease. It may be that certain horses have an innate susceptibility to IAD. In this case, anything that sets off inflammation, such as viral respiratory disease, can put in motion a vicious spiral that results in IAD or heaves.

Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology

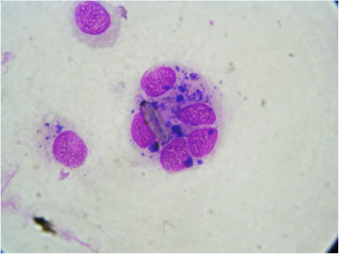

The common link between heaves and IAD is airway inflammation. In horses with heaves, the inflammation that we see on a lung wash, otherwise known as a bronchoalveolar lavage or BAL (see below) is due to cells called neutrophils, whereas in horses with IAD, the culprits may be neutrophils, mast cells or a combination of the two. Horses rarely have eosinophils as the inciting inflammatory cells, unlike cats and humans with asthma who commonly have high levels of eosinophils in their airways. We know far more about what happens on a microscopic basis in the lower airways of horses with heaves than we do about horses with IAD. Horses with heaves develop increases in airway smooth muscle, fibrous tissue, epithelial tissue and mucus, all of which contributes to the marked bronchoconstriction (narrowing of the airways) that results in abnormal breathing and air hunger. Although we can reverse bronchospasm due to abnormal smooth muscle contraction with drugs such as albuterol, and we can reduce mucus production with the use of corticosteroids (see below), the fibrosis and epithelial thickening are difficult to reverse, and abnormal lung function in horses with overt heaves can still be detected even when the horses are in remission.

When horses have chronic, long-standing airway dysfunction, as with heaves, they often develop abnormal breathing patterns at rest. The time that they spend breathing out (expiration) is usually prolonged, and they often develop hypertrophied external abdominal oblique muscles that are used for pushing air out of the lungs. Just as a bodybuilder develops an exaggerated look from overuse of specific muscles, a horse with heaves develops a heave line from muscular overuse during breathing. Some horses become quite thin when they have chronic heaves. We know from studies in our laboratory that these horses burn the same amount of calories that they would if they were trotting all day and all night. It would be impossible for them to eat enough to satisfy their caloric needs.

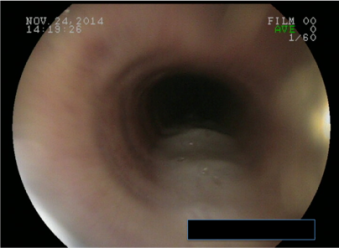

While we know less about the pathology of IAD, we do know that they produce excessive amounts of mucus, which we see both on endoscopy and BAL cytology. Because most horses with IAD have airway hyperreactivity, we can surmise that they have either overly active airway smooth muscle or excessive amounts of smooth muscle in their airways. A recent study showed that airways of a vast majority of actively racing horses have neutrophilic inflammation of the small airways as well as smooth muscle hyperplasia. The distribution suggests that the inciting agent is inhaled; this correlates well with the clinical data showing that airway inflammation is associated with high levels of particulates, including endotoxin, beta glucans, ammonia and other airway irritants.

Why Does it Matter?

It’s not hard to understand why heaves matters for a horse. When a heaves-affected horse can hardly walk from the barn to the paddock, it’s clear that the horse has a poor quality of life and no athletic ability. But what about the horse with IAD? If it were just a cough or an occasional drippy nose, IAD would be annoying but nothing else. The problem, though, is that IAD affects athletic function. Horses with constricted airways have trouble getting enough air out of their airways, and this eventually leads to uneven ventilation of the lungs. Parts of the lungs get enough oxygen, and other parts do not. This leads to hypoxemia (low blood oxygen levels) during exercise. Low blood oxygen levels in turn lead to fatigue, which can contribute to injury in addition to poor performance. Moreover, there is emerging evidence that shows horses with IAD have a much higher risk of eventually developing the more severe disease, heaves. If we recognize and treat IAD at an early stage, we have a better chance of preventing severe and debilitating diseases later in life.

Ready to Find Out More?

Download Dr. Mazan's Equine Respiratory Health e-book for a detailed understanding of equine respiratory health.